Tagged with 'Natural pearls'

The very latest news, musings and opinions from the world of Winterson. Quite simply, a celebration of a jewellery, fashion, culture and the business behind luxury.

-

La Peregrina - Famous Pearl Jewels

La Peregrina - Famous Pearl Jewels

The legend of La Peregrina, one of the world’s most famous natural pearls, suggests that it was found in the mid-16th century near the island of Santa Margarita in the Gulf of Panama by an African slave, who was rewarded for his find with freedom.

At the time this extraordinary pear-shaped pearl was also one of the largest ever found, measuring approximately 17.5mm by 25.5mm and weighing over 11 grams before it was cleaned and drilled.

Don Pedro de Temez, the administrator of the Spanish colony, recognised the pearl's importance and brought it to Spain, where he gave it to the future king - Philip II of Spain. At this time the pearl began an incredible journey of ownership and it remains today one of the oldest and best documented historical jewels.

Philip presented with La Peregrina to Mary I of England, his future wife. Mary wore the pearl as a pendant suspended from a brooch, a jewel she can be seen wearing in a series of portraits from the period. After Mary’s death in 1558, the pearl was returned to the Spanish court where it remained for 250 years, and was worn by the wives of Kings Phillip III and IV.

Image 1: Mary Tudor, original artwork by Antonis Mor 1519-1575

Image 2: Elizabeth Taylor, c.1972

In 1808, when Napoleon installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain, the pearl found its way to France. In 1848 the pearl finally made its way to England into the Estate of James Hamilton, Duke of Abercorn. It was during this time it was given the name La Peregrina, which means the “Pilgrim” or “Wanderer”.

La Peregrina remains one of the largest perfectly symmetrical pear-shaped pearls in the world. The Hamiltons sold the pearl for $37,000 at Sotheby’s in 1969 to Richard Burton, as a Valentine Day's gift for Elizabeth Taylor.

It was the exquisite heirloom that sealed one of Hollywood's most tempestuous love stories. Drop and pear-shaped pearls are often made into pendants, but during its history La Peregrina was worn as a brooch, a pendant to a necklace, the centrepiece of a necklace and even a hat ornament. Taylor commissioned Al Durante of Cartier in 1972 to design a ruby and diamond necklace mount for the pearl. The complete piece is quite stunning and truly one of a kind.

When Taylor died, La Peregrina was sold at auction by Christies in 2011 to raise funds for the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, which was established by Taylor to help provide direct services throughout the world for people living with AIDS.

Christies estimated the value of La Peregrina to be between $2 million and $3 million, making Lot 12 the second highest valued lot of the auction. In a fitting tribute to the memory of Elizabeth Taylor, the auction of legendary jewels surpassed all expectations, with the sale of La Peregrina for $11,842,500 creating two new world auction records for a historic pearl and for a pearl jewel.

Where, we wonder, will the next stage of its historic journey be taking the Wanderer to? -

The Hope Pearl - Famous Pearl Jewels

The Hope Pearl - Famous Pearl Jewels

From time to time in The Journal, we explore the origins and stories around famous pearls and items of pearl jewellery. In this article, we continue to share our fascination for this most stunning of gemstones, with the extraordinary Hope Pearl.

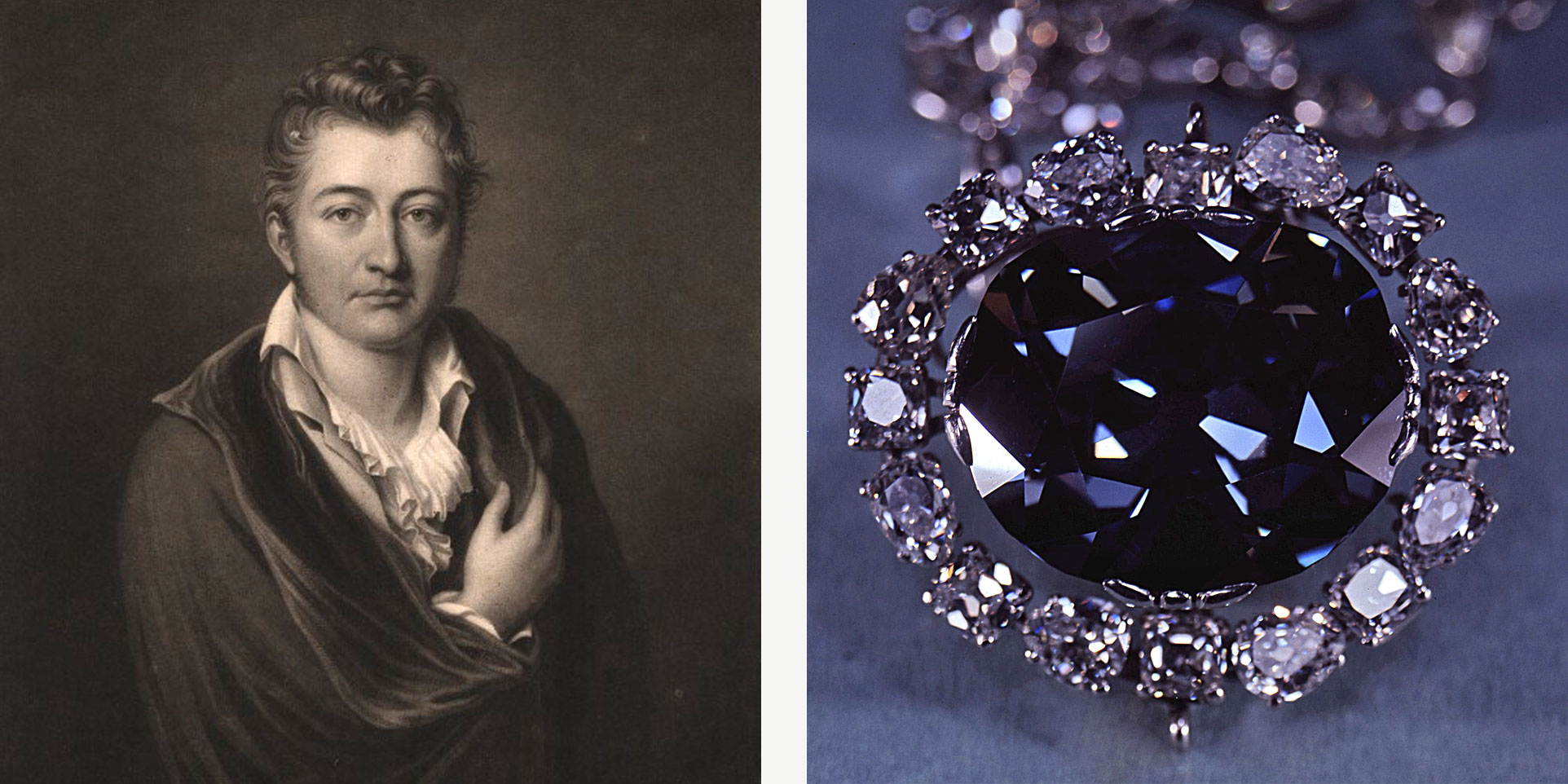

Believed at the time to be the largest natural saltwater pearl ever discovered, the Hope Pearl was named after its owner Henry Philip Hope. Hope (1774-1839) was an Anglo-Dutch gem collector, who acquired many renowned gemstones and diamonds for his collection, including the famous blue Hope Diamond and approximately 148 natural pearls of significant size.

Image 1: Henry Philip Hope, by Thomas Goff Lupton, after Bouton, 1823

Image 2: The Hope Diamond

The Hope Pearl was one of Henry Philip Hope’s first acquisitions as he set about building his collection of gems and jewellery. The Hope Pearl was believed to have been possibly acquired by Tavernier and sold to King Louis XIV in 1669, before being subsequently sold to Hope, around 1795. The pearl was included in a catalogue of his collection that was published by Bram Hertz in 1839, the year that Henry Philip Hope died.

Its exact origin is unknown, but it is likely, given the period when it was discovered, that the Hope Pearl was an ‘oriental’ pearl. It was perhaps found in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea or the Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka, which were the traditional centres of the pearl fishing industry for over 4,000 years.

Weighing around 1,800 grains (or 450 carats), the Hope Pearl is a blister pearl. The pearl would have formed on the inner surface of the mollusk's shell. This location is still visible on the surface of the gem, although it has been polished to resemble other parts of the pearl’s surface.

It is its size and cylindrical drop shape that makes this pearl so unusual. Natural blister pearls are thought to form as pearls within the mollusk's mantle tissue, before breaking free and being pressed into the shell. Cultured blister pearls today are usually hemispherical, with a layer of mother of pearl being used to create the flat back of a mabe pearl.

Measuring approximately two inches by four inches, and ranging in colour from greenish-gold on one end to white on the other, the Hope Pearl contributed significantly to an explosion of interest in baroque pearls and baroque pearl jewellery in the late 16th to 17th centuries.

The popularity of baroque pearls stemmed from their unique qualities of shape and colour, with master jewellers creating extraordinary gems in forms that the pearls themselves suggested. The Swan Pendant, now at the Hermitage State Museum in St Petersburg, and The Canning Jewel, part of the Victoria & Albert Collection, are two of the most famous examples.

Hope had the pearl mounted in a pendant setting in the shape of a crown, and featuring rubies and diamonds. Now in private ownership, the Hope Pearl has been exhibited internationally including at the Natural History Museum in London and the Smithsonian in New York. -

What are the classic jewellery designs for pearls?

What are the classic jewellery designs for pearls?

It has long been known that the pearl has played a central role in jewellery, with some of the earliest recorded fragments of a pearl necklace being dated to the 4th century BC. What are the most popular and successful designs of classic jewellery that pearls have been used with - and how are they being updated today?

The pearl was believed by numerous cultures to symbolize purity and to offer protection, as well as being indicative of their owner’s social position. Their beauty and rarity meant that the gems held an almost mythological, and certainly significant financial status.

The Timeless Classic

There are many examples through the ages of how our love for the pearl has influenced the wearing, adornment and design of the classic jewellery that we love today.

In China as early as 2300 BC, pearls were considered appropriate gifts for royalty, representing not just the integrity and loyalty of the giver but also the wisdom and virtue of the wearer. Julius Caesar passed a law in the 1st century BC, which determined that pearls should only be worn by the ruling classes.

In India, it is still believed that the pearl confers calm on its wearer, attracting wealth and good luck. The gem was a favourite of Indian royalty, most notably the Mahraja Khande Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, whose seven-strand necklace was legendary even within a culture where extraordinary gems were plentiful – so much so that the famed necklace gained a name of its own: the Baroda Pearls.

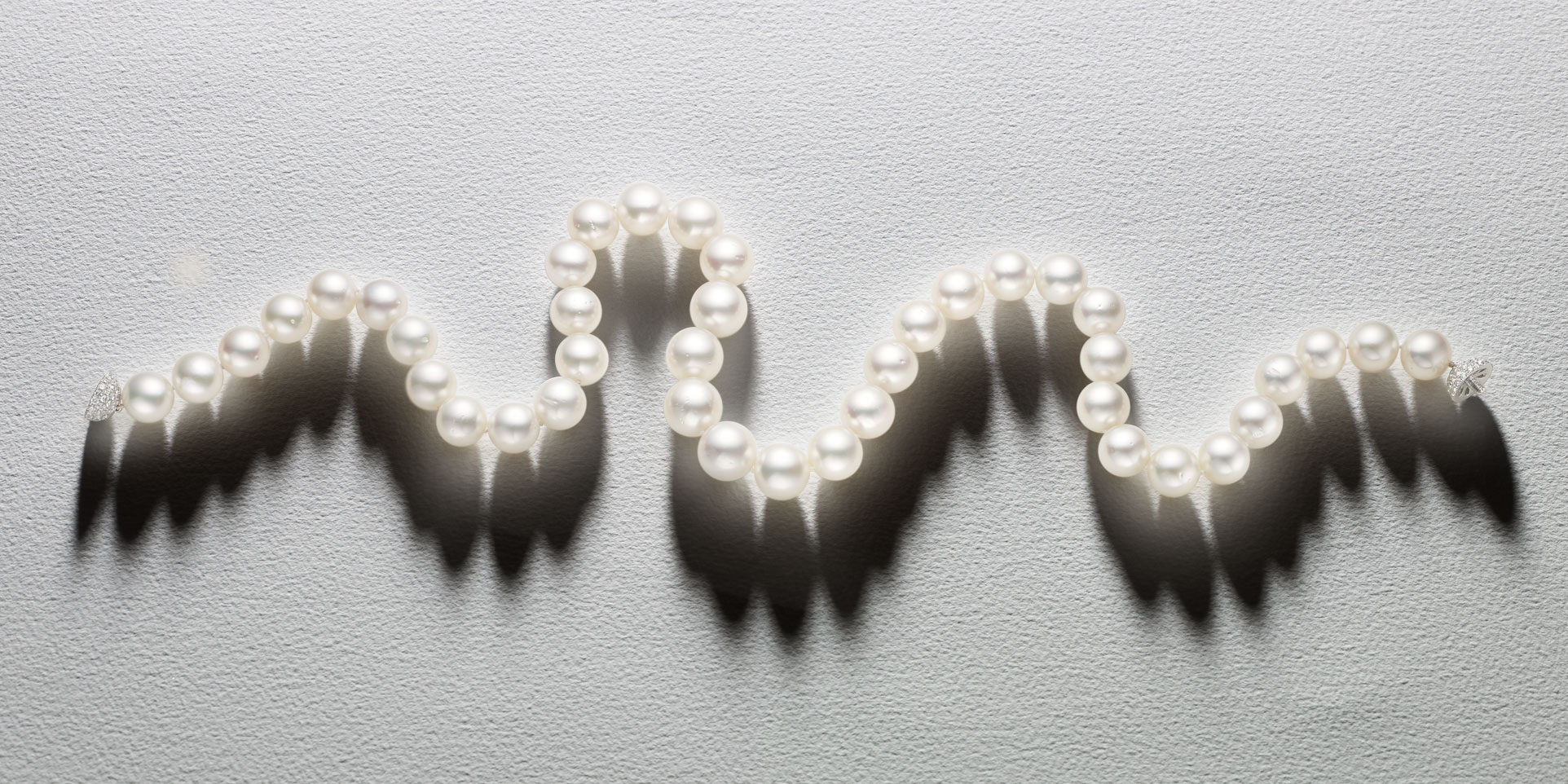

Image: A Winterson South Sea pearl and pave diamond clasp necklace

Their extravagant value lead to the pearl playing an important role in trade, which only increased once they were discovered in Central and South America in the 15th century, a discovery which led to the so called Pearl Age.

As a visible symbol of wealth, the demand for pearls escalated, particularly in Western Europe, where royals and aristocrats increasingly emulated their peers in China, India and the Arab states, commissioning elaborate pearl necklaces, earrings, bracelets and brooches.

By the 19th century, demand for pearl jewellery was so high that the supply of natural pearls began to dwindle to the point today where historic pieces of natural pearl jewellery are so rare they can fetch high six or seven figure sums at auction.

The Pearl Necklace

As a result of the way that they reflect light to the face, strands of pearls have become the most popular form of classic jewellery over the ages. The more strands in a necklace, the greater that the necklace reflected the wealth of its owner.

Image 1: Blush Sunrise Necklace

Image 2: A portrait miniature of Emma Ostaszewska née Countess Załuska, ca. 1850s

The lustre of the gems was often preserved by having Victorian maids wear the necklaces during the day to keep the pearls warm and radiant for their mistresses.

With the arrival of the cultured pearl, the status of the gem has shifted over the 20th century, becoming more widely accessible. The multi strand pearl necklace remains an enduring piece of classic jewellery that actresses, society ladies, designers and jewelers such as Winterson prize winner Bella Mung continue to revisit.

Our pearl specialists individually select and grade each strand that makes up a Winterson necklace, often viewing and reviewing pearls throughout the day to be aware of the impact of shifting light on the overtones and lustre of the pearl. Our necklaces are available in multiple lengths, colours, and different types of pearls, including Akoya, Freshwater, South Sea and Tahitian. Read our Buying Guide to choosing a necklace to learn more.

The Pearl Stud

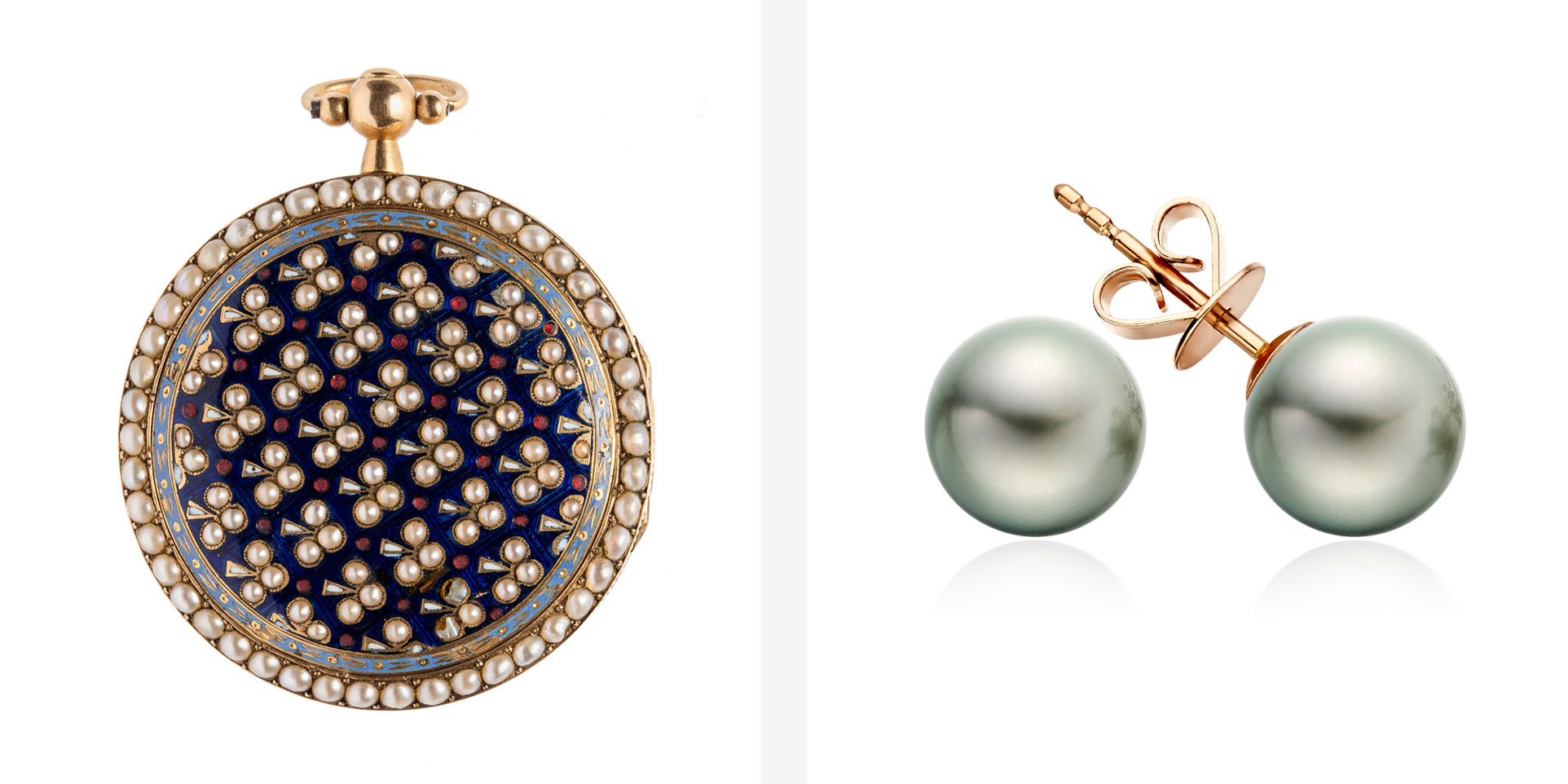

After the pearl necklace, pearl studs form another cornerstone of a woman’s classic jewellery wardrobe. The legendary Coco Chanel was well known for her enduring love of these beautiful gems,which she wore prodigiously (real and fake together).

Although she favoured the monochrome white pearl necklace, once famously declaring “a woman needs ropes and ropes of pearls", her single pearl clip earrings were almost as significant a part of her iconic image.

Image 1: Pocket watch of gold, with enamel and oriental pearls, 1800

Image 2: Green Grey Tahitian Pearl Stud Earrings in Rose Gold

The pearl studs at Winterson are available in a wide choice of colours, sizes from 6-12mm , types of pearls and finished with 18 carat white, yellow and rose gold earring posts and butterflies.

The Pearl Drop Earring

In an era where natural pearls, with all their unique forms and qualities, were the stones that were used in classic jewellery, the popularity of the drop shape is unsurprising. Vermeer’s famous Girl with a Pearl Earring provides the archetypal blueprint for the freshwater drop earring, a classic style that has most recently been adopted by the current Duchess of Cambridge.

Image 1: Yellow Gold Diamond Leverback And Freshwater Pearl Drop Earrings

Image 2: The Girl With The Pearl Earring, Johannes Vermeer, 1665

Natural pearl drops continue to fetch high sums at auction, as the sale of a pair of earrings owned by Empress Eugenie of France, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, amply demonstrated. Fetching $3.3 million, the drops were then promptly reset for their new owners by American high jeweler Lee Sieglson, reflecting that the value was paid for the pearls rather than their original setting.

The Seed Pearl Ring

Seed pearls gained popularity in Georgian and Victorian jewellery, where they often accented the frame of rings and earrings in the same way that diamond pave does today.

Image 1: Funeral Ring, Landscape and Temples, 18th Century

Image 2: Beau Seed Pearl and Enamel Ring with Yellow Gold

Often seen as part of mourning jewellery, set around painted portraits or landscapes or offset by washes of enamel, this era of jewellery formed the basis of inspiration for Alice Cicolini’s Beau collection for Winterson.

The Pearl Brooch

Seed pearl pave, where lines of these wonderful tiny pearls are set in single or multiple rows, also offered a stylish way for jewellers to incorporate the pearl in brooches. This form of jewellery became highly popular in the 19th century as a decorative jewel, rather than as a functional object which was the original purpose of the brooch.

Although their popularity has waxed and waned over the years, it appears as if the brooch may be increasing in popularity again as fashion brands and jewellers alike seek new surfaces for jewels to come alive.

Perhaps pearls may also find their way onto these new generation designs. The Duchess of Cambridge might have recently signalled the reinvention of this classic jewellery design at a recent state visit, wearing the Queen’s triple pearl and diamond leaf pearl brooch with the stunning Collingwood Pearl and Diamond drop earrings which she often favours. -

Bejewelled Treasures from the Al Thani Collection

Bejewelled Treasures from the Al Thani Collection

Winterson's Creative Director Alice Cicolini takes a retrospective glance at the celebrated Al Thani collection of jewellery. The exhibition, which first appeared in Bejewelled Treasures at London's Victoria & Albert Museum, is set to open this Spring at the Grand Palais, Paris in March 2017.

The Al Thani Collection is a unique collection of jewels from an unusually broad chronological period that spans the Mughal period of the early 1600s to the present day. With such a diverse group of objects to select from, the V&A exhibition's curator Susan Stronge paints an impressive, if partial, picture of the development of Indian jewellery techniques and tastes.

Jewellery in Mughal society

The focus in the early part of the exhibition emphasises the almost ubiquitous presence of gemstones and jewellery throughout the Mughal court: from fly whisks and wine cups, to backscratchers and huqqa bases. The prevalence of precious and semi-precious gems led visitors to India in this period to remark on the magnificence of courtly life, its gem-encrusted thrones and imperial bodies that sparkled with jewels.

Hindu rulers lived under clear instruction as to the importance of establishing of an almost God-like regal body politic, through dress, jewellery and grooming. This remarkable profusion of jewellery, which their Mughal successors appeared to share, went far beyond the ruling classes to encompass men and women at all levels of society.

Image 1: Spinel and pearl necklace

Image 2: Silk sword sash with jewelled gold fittings

This is very revealing of the important role that jewellery played, not simply in the creation of status, but in what modern historian Daud Ali has described as “the spiritual and literary life of Indian societies” and the “association of jewels with light, virtue and beauty”. It is in early Sanskrit texts such as the arthashastra and brihatsamhita that the spiritual, cultural and healing values of stones, grading & assessment and jewellery techniques began to be established.

A love for pearls and gems

Many of these central tenets of gemlore still inform contemporary Indian jewellery making and buying practice, today with the navratna, or nine-stones, continuing to play a alismanic role in jewellery culture. Of these, the five great stones, or mahararatnani, - diamond, pearl, ruby, sapphire and emerald - dominate Indian jewellery culture as they did several hundred years ago.

As a result, for pearl lovers the Bejewelled Treasure exhibition offers a wealth of extremely fine examples. Visitors to India frequently remarked on the ropes of pearls that covered the bodies of both men and women, rulers and lesser subjects alike, upon which it would have been difficult to place a price. The arthashastra particularly notes methods for grading pearls, and the types of necklaces into which they could be strung, including one gravity-defying necklace of 1,008 rows.

It may be that one of the reasons that visitors saw pearls worn by non-royal courtiers was that, much like their British equivalents, Indian rulers charged their servants with wearing their pearls during the day to keep them both warm and luminous. Although the geographical proximity to the pearl fishers of the Arabian Gulf and Sri Lanka would have given Indian rulers greater access to pearls than some of their European peers, the pearl was still regarded a symbol of status. Some rulers were believed to drink powdered pearls as an aphrodisiac, and the Sanskrit word for pearl, manjari, means “bud” denoting the sensuality the gem has come to symbolise.

Image 1: Diamond turban jewel made for the Maharaja of Nawanagar

Image 2: Cartier Brooch set with emeralds, sapphires and diamonds

Other notable aspects of the exhibition include several exquisite examples of spinel, a stone which has long been celebrated in the subcontinent whilst remaining relatively unknown in the West. A combination of increasing scarcity, the price of tourmaline, the prevalence in the market of glass-filled and heat treated ruby and the spinel’s relatively low profile, however, marks this gemstone out as a major jewellery trend.

One of the main centerpieces of the show, and one of the few pieces in the exhibition not from the Al Thani Collection, is the Timur Ruby, rather abstractly titled since it is neither a ruby nor was it ever owned by the famous Indian ruler. Now part of the collection of Queen Elizabeth II, the stone was given to Queen Victoria by the East India Company in 1851, and then set in gold, enamel and diamonds by Garrards in 1853. The gem itself demonstrates the significant value placed on these stones by a succession of Mughal rulers, engraved as it is with the names of five royal owners from Jahangir, son of Akbar, in 1612 to Sultan Nadir in 1741.

Contrasting traditional with modern

The Timur Ruby also demonstrates the differing understanding of value that remains central to much of India’s more traditional jewellery making practice. Unlike Western cultures, where brilliance, fire and perfect precision cutting constitute extraordinary gems, the Indian subcontinent holds true (in its more traditional manifestation) to the notion that a stone’s natural character and form – its scale, luminance, colour and clarity – are what defines its beauty.

One of the main techniques that the exhibition focuses on is kundan, the practice of using highly refined gold to set natural, irregular stone shapes within fine, symmetric settings. Its aesthetic is one that has come to define traditional Indian jewellery, and its abandonment by India’s contemporary high jewellers is one of the most notable characteristics of their perceived modernity.

It is the quite clear break with traditional jewellery making practice that the exhibition makes visible, which is one of the show’s most interesting features. Alongside the rejection of traditional setting techniques, it is the widespread preference for platinum (with yellow gold removed to the reverse or interior structure of these new jewels) that has seemed to define “modernity” in contemporary Indian jewellery.

Western influences

Certainly this trend is most evident within the fertile Art Deco period that saw such a volume of commissions from Indian rulers to luxury high jewellery houses in the West such as Cartier, Boucheron, and more recently JAR, and more recently in contemporary jewellery from India itself.

Image: Gold and diamond hair ornament

Stronge implies that the increased cross-fertilisation with Western tastes has resulted in a loss of regional difference across Indian jewellery, although it's perhaps difficult to conclude about a wider trend from the prism of a very personal selection of objects. It is certainly true that the contemporary jewelers that Al Thani has favoured lean very heavily towards the language of Westernised Indian-ness that Cartier, his Indian clients, and the many other 1920s Western jewellery houses who operated in the country, helped to establish.

The exhibition catalogue relates a lovely vignette of Jacques Cartier’s first visit to India as part of the Delhi Durbar of 1911, marking the coronation of George V as Emperor of India. Cartier had brought, Stronge relates, a selection of jewellery for women, but rapidly realized “the enormous potential of this market was that the princes bought mostly for themselves”.

The legacy of the Al Thani treasures

Perhaps what makes this exhibition so unique in its presentations of high jewellery is that the majority of the pieces chosen have been created to be worn or used by men rather than women, and this in itself is something worth visiting for.

As masculine jewellery cultures diminish so dramatically across the world, the exhibition profiles a dying way of life – both that of the makers, as their traditional arts appear to fade from fashion, and the wearers, and ways of wearing, that these extraordinary gems represent. -

A Peek at the Pearls of Carl Linnaeus

A Peek at the Pearls of Carl Linnaeus

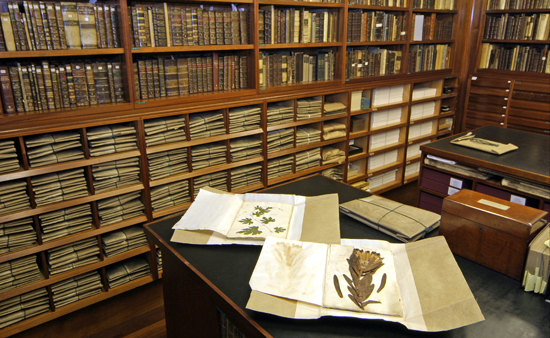

The world of pearls can hold many surprises, but it is not everyday that you have an opportunity to view a historic treasure secured safely beneath the streets of London.

The experimental pearls of famed Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus are about to join the forthcoming Pearls Exhibition at the V&A and so we jumped at the chance to see these early successful attempts to culture a spherical pearl in close up.

CARL LINNAEUS

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) is best known for his method of classifying organisms that uses two latin names to represent the genus and the species, for example 'Homo Sapiens'. This taxonomy is conventionally used today to describe and classify the hierarchical relationships of animals, plants and insects to each other.

Linnaeus' collections of specimen organisms, including dried flowers, insects, fish and molluscs are unique and are still a primary reference point for scientists to determine if they have found a new species.

Following his death, the Linnean collections were purchased by Sir James Edward Smith in 1784 and transported to London, where they remain today.

THE LINNEAN SOCIETY

In 1788, Smith also founded The Linnean Society to provide a forum to discuss and promote the study of natural history.

The Linnean Society is the world's oldest active biological society. It was at a meeting of the Society in 1858 that papers by Charles Darwin were presented outlining the theory of natural selection and evolution.

The collections were obtained by the Society in 1829 and are today securely held in a vault below the courtyard of Burlington House, Piccadilly in central London. Leather bound books, old parchment folders and specimen trays line the carefully curated shelves and drawers.

Also in the strongroom was a very rare (and valuable) signed first edition of Charles Darwin's 'Origin of the Species' - a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see.

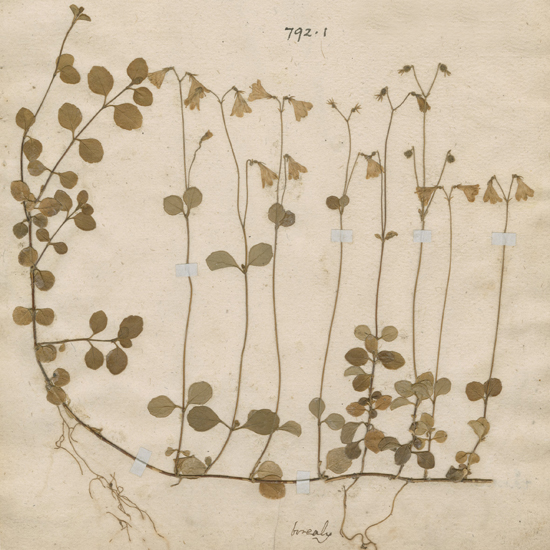

LINNAEA BOREALIS

Carefully wrapped in parchment was this original specimen of Linnaea Borealis, a wildflower of northern and alpine origin that has a distinctive double twin flower shape. The flower is named after Linnaeus as it was a favourite of his whilst travelling in Lapland.

As well as having a beautiful white pink flower, Carl Linnaeus fell in love with the wildflower for the way that it grew persistently in the undergrowth and its ephemeral, short-lived life. These were two symbols that he felt were important in his own life and portraits of Linnaeus, including the one above, and in the Society all feature the Linnaea Borealis.

This little flower has a special meaning for Winterson as it was an inspiration for our own flower motif, also honouring its link with Linnaeus and his early achievements in culturing pearls.

LINNAEUS AND PEARLS

Linnaeus declared in 1761 that 'he had heard of people who made gold, but had never heard of any who could make pearls'. Describing the lengthy and time-consuming efforts to find natural pearls that he had seen in Purkijaur, Lapland, Linnaeus believed that a technique for culturing pearls existed that would be more effective and profitable for Sweden.

Linnaeus started to experiment with 'Unio Pictorum', a species of freshwater mussel called the Painter's mussel. This mussel was named as traditionally its shells were used by painters as convenient receptacles for mixing paint.

His technique was a variation of an old Chinese method for producing blister pearls. Drilling a hole in the mussel's shell, Linnaeus inserted a small granule of limestone between the mantle and the shell to help produce a free spherical pearl inside the mussel.

The mussels were returned to the riverbed for six years to produce what is regarded as the world's first spherical cultured pearls. They are indeed historic and fascinating to view.

Linnaeus' method is also based on an old misunderstanding that pearls are created with a grain of sand. We know now that a response to illness or a parasite is the more likely explanation for the growth of natural pearls in an oyster or mussel.

These experimental pearls were not ultimately the source of riches that Linnaeus had hoped for, but he was enobled by the King of Sweden for his efforts taking the title von Linné. The pearls, a patent and Linnaeus' secret were sold to a Swedish merchant named Peter Bagge, but nothing came out of this venture.

Another Londoner Sir John Hunter is recorded as having attempted to culture freshwater pearls in his ponds at Earl's Court Manor House using a similar method to Linnaeus, but it was left to a different Englishman William Saville-Kent to make the next break-through in pearl culturing.

SEE THE LINNAEUS PEARLS AT THE V&A

We would to like thank Elaine Charwat, Deputy Librarian of the Linnean Society for her fabulous help in showing us Carl Linnaeus' pearls.

The pearls themselves are on display soon at Pearls, the V&A's new exhibition. Not to be missed...

-

Pearls Exhibition at the V&A Museum

Pearls Exhibition at the V&A Museum

With much excitement and anticipation, the Pearls exhibition at the V&A Museum opens later this month in London.

PEARLS EXHIBITION AT THE V&A

Promising to be one of the biggest Autumn shows, the exhibition will show off the luxurious qualities of some of the world's most unusual and valuable pearls and jewellery, as well as exploring the unique heritage and impact on popular culture of this beautiful gem.

We are very fortunate to be able to ask Beatriz Chadour-Sampson and Hubert Bari, the curators of the Pearls exhibition, about the show and what a visitor can look forward to. We would like to thank them, the V&A and the Qatar Museums Authority for their support with this article.

Here are Beatriz and Hubert's thoughts on 'Pearls'.

How special has this exhibition been for you and to curate? What did you hope that its visitors may learn about pearls?

From all gems, it is the most unusual as the natural pearl is produced by living animals. Even cultured pearls after human intervention are created by nature. Visitors will be amazed to learn that, in principle, any mollusc can produce a pearl from the giant clam to the land snail, and they will be dazzled by the variety of shapes and colours of pearls.

The history of the trade of pearls between continents is fascinating, and how East and West share the same passion for pearls.

Pearls have a unique symbolic significance and mystique. Can the pearl claim to be the world's favourite gem?

Incredibly, pearls have created a global fascination over millennia, like no other gem. There is something magical about pearls, their beauty lies in their perfection of form and most of all lustre. They are born in the form that nature made them with a natural sheen.

Pearls have always been a symbol of femininity. Maybe this is the reason why the fashion for pearls continues today.

The exhibition showcases many famous examples of pearl jewellery, many styles of which are still being referenced today in popular culture. Have we already seen a 'golden age' of pearl jewellery design or is the pearl a gem that will be constantly reinvented?

Yes, as no other gem has been worn as consistently, as pearls. Pearls are neutral and versatile, appropriate for any occasion. In previous years jewellers have shown a persistent, if not renewed interest in creating new designs with pearls.

What is the most striking or surprising aspect for you about the history of the pearl?

The fascination for pearls and wish to wear these beauties of nature transcends cultures and borders. The similarities in the myths and legends surrounding the pearl in East and West are astonishing. Pearls mark authority and power, symbolize prosperity and on a more personal note they are associated with joy at weddings or tears as a sign of mourning.

Natural pearls have undergone a renaissance in the last decade, achieving spectacular prices at auction, and cultured pearls are being produced in better, more diverse and beautiful qualities. What does the future hold for this gem?

The future of the pearl depends on so many factors, not least the condition of our seas. Natural pearls are simply too rare and expensive, only affordable to the very few. Today China produces such quantities of cultured pearls of inferior quality, that they are endangering the pearl market. Whilst they give great care when creating one pearl from an oyster, the Chinese produce 50 in one mussel, at low cost in rice fields or near housing estates. In South East Asia the farms which produce the beautiful South Sea pearls are experiencing not only financial difficulties but the effects of pollution and for these reasons their future remains uncertain.

The desire for pearls has been so insatiable that imitation pearls have existed over centuries and their advocate in the 1930s Coco Chanel was instrumental in reviving the fashion for pearls and revived the industry at a time when this was unthinkable. No one can tell what the future will hold for this beautiful gem, but the fashion for pearls endures.

The 'Pearls, V&A and Qatar Museums Authority Exhibition', runs from 21 September 2013 to 19 January 2014 as part of the Qatar UK 2013 Year of Culture.

To learn more about the exhibition, visit the V&A website here.

-

Fascinated by Pearls: William Saville-Kent

Fascinated by Pearls: William Saville-Kent

One of the most influential and unsung pioneers of the modern day cultured pearl industry was an Englishman called William Saville-Kent.

Many popularly associate Kokichi Mikimoto with the discovery of the technique to culture a spherical pearl in the early 20th century. But the intriguing truth of the race to discover how to mimic nature's process of creating a spherical pearl is far less clear, even today.

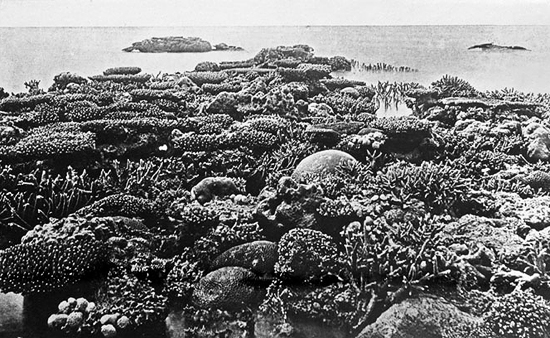

By the late 1890s, the pearling industry in Queensland, Australia was in real trouble. Although the sixth largest industry in Queensland in 1884, its export value had almost halved within the next 5 years. The coral and oyster beds off the northern coasts of Australia and the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea were sadly being depleted by divers and fishing fleets in search of valuable natural pearls and mother-of-pearl shell for use as buttons.

William Saville-Kent was a marine biologist with considerable experience of surveying and managing fish and oyster stocks. Over a period of 15 years, he was appointed by the British Colonial Government as Inspector of Fisheries in Tasmania (1884-87) and Commissioner of Fisheries for both Queensland (1889-92) and Western Australia (1892-95).

One of his main roles was to report on the increasingly difficult economic and environmental situation facing the pearling industry, introducing systems for licensing fishers, regulations for protecting the smaller sizes of the catch and creating protected government reserves for the longer-term sustainability of this natural resource.

Saville-Kent was also a practical naturalist and was the first to recognise the difference between the silver and gold-lipped Pinctada maxima South Sea pearl oyster and the black-lipped Pinctada margaritifera cumingii Tahitian pearl oyster.

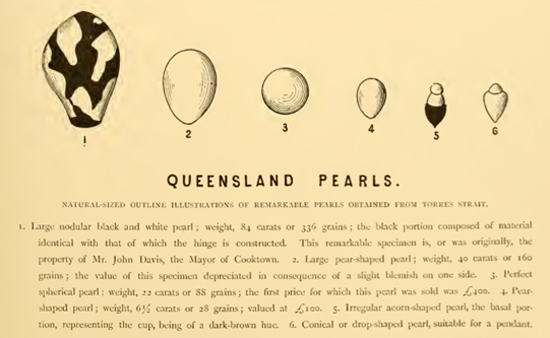

Beginning his experiments in 1889 at Thursday Island in the Torres Strait, the centre of the Queensland pearling industry, Saville-Kent would have been very aware of the impact that his work could have on the industry that he was so fascinated with. In this extract above from his 1893 book The Great Barrier Reef, he describes a single perfect spherical pearl (number 3) with a market value then of £400, worth approximately £40,000 adjusted for inflation today.

By 1891, Saville-Kent had successfully produced a number of cultured blister pearls and exhibited these in London. This was two years before Mikimoto had cultured five semi-spherical pearls in Japan.

Returning from London in 1905, with a syndicate called 'The Natural Pearl Shell Cultivation Company of London', a commercial cultured pearl farm was established near Torres Straits. Saville-Kent and his financial backers were convinced that they had the secret of how to produce a spherical cultured pearl.

There were by now others, however, with the same objective and this unique commercial and scientific race had begun...

-

Pearl Fishing for the Oldest Natural Pearl

Pearl Fishing for the Oldest Natural Pearl

Earlier this year, French researchers discovered an ancient natural pearl at a coastal archaeological site in the Umm al-Quwain, one of the emirates of the United Arab Emirates. Confirming the finding with carbon-dating, the team from the Laboratoire Archéologies et Sciences de l'Antiquité has shown that pearl fishing and diving was taking place in the Persian Gulf as early as 5,500 BCE, far earlier than previously thought.

Before this important discovery in June 2012, it was thought that the oldest pearl in the world was the Jomon pearl, a Japanese archaeological find dating back more than 5,000 years old.

The natural pearl oyster beds of the Persian Gulf were a significant part of economic and cultural life for centuries, with Phoenician, Persian and Arab dhows and divers searching the sea waters of the Gulf for pearls. Bahrain was the centre of pearl fishing, and even today the emblem of the state includes two boats and a pearl.

The main pearl-producing oyster in the Gulf is Pinctada radiata, a small mollusc that can produce a white creamy colour pearl of around 4-6mm in size. Pearl divers would dive all day to depths of around 20 metres in search of these coveted gems.

The economic importance of pearls to the region is particularly apparent as pearls were its main export until as recently as the 1930s, when the oil industry and exploration in the Gulf states expanded and gave pearling fleets an alternative livelihood. It was also around this time that competition from the cultured Akoya pearl industry in Japan was increasing.

The CNRS team's discovery is surprising for extending the timeline of the region's association with pearls and for showing how pearls played a special role in society. The Umm al-Quwain pearl was found in a Neolithic grave site and might have been placed on the deceased's face or upper lip as part of a funeral ceremony.

Several Gulf countries such as Kuwait and Bahrain are interested in reviving their traditional pearl industry, but for now the Umm al-Quwain discovery is a reminder of a past age.

-

Blue Pearl Secrets of the Abalone Sea Snail

Blue Pearl Secrets of the Abalone Sea Snail

Abalones are large sea snails with a secret. Brown and grey on the outside, and covered in seaweed, they hide a world of iridescent blue pearl colour inside their shells.

Abalones are a variety of marine gastropod, resembling a typical garden snail and carrying a single spiralled shell on its back. They live in shells that are up to 20 or 30cm in size and can survive in both cool and warm saltwater tidal zones.

Also considered a delicacy by some, Abalones are typically found off the coasts of Western USA, Mexico, Japan, Korea, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Although most live for 10 to 20 years, they can reach as much as 40 or 50 years in age.

Along with Conch snails and Melo melo, Abalones are also one of the few gastropods that are capable of producing pearls. As with pearls that are formed by a mollusc such as an oyster, an Abalone's pearls are made by depositing thousands of layers of an organic substance called nacre.

The surface of their inside shell, also called mother-of-pearl, shimmers with a kaleidoscope of blues, greens, pinks, silver and purple. The dark lines that weave across the surface of the shell, and linking its colours and texture together, are made with conchiolin, an organic protein that helps form a pearl's nacre.

Natural Abalone pearls are very rare. The unique colours of these blue pearls and their baroque horn shapes are highly sought after by jewellery collectors. One of the largest natural Abalone pearls ever found is the Big Pink Pearl, which was valued in 1991 at $4.7 million. Symmetrical round Abalone pearls are even more unusual and can take many years to form.

Attempts to produce cultured pearls with Abalones have been recorded since the late 19th century. The principal Abalone pearl farms today are in California and New Zealand, where the native paua is used to produce beautiful blue pearl mabe.

Culturing a saltwater pearl requires years of investment, technique, experimentation and pristine environmental conditions. But the challenges for Abalone pearl farmers are even harder as the animal is particularly sensitive to injury.

Blue pearl mabe are more frequently cultivated by pearl farmers as the procedure for making a blister pearl is more successful and less invasive to the Abalone. These beautiful cultured mabe pearls can be made into a unique collection of pendants, rings and earrings.

It would be almost impossible today to collect a sufficient quantity of round Abalone pearls to match and make into a conventional pearl necklace. Imagine how amazing and unique the colours of that piece of jewellery would be! -

The Rare Pink Pearls of Queen Conch

The Rare Pink Pearls of Queen Conch

Pearls can be formed by different types of molluscs other than saltwater oysters and freshwater mussels. One of the most celebrated and rarest types of natural pearls are the delicate pink pearls of Queen Conch. Shyly peeking out from underneath this shell are the eyestalks of an endangered mollusc that lives in the shallow and warm waters of the Caribbean Seas.

Queen Conch, also known as Lobatus gigas or Strombus gigas, is one of the largest living molluscs and can grow up to 30cm in size. Believed to have been around since the Pliocene Epoch, some 2.5 to 5 million years ago, Queen Conch has an average lifespan of between 20 and 30 years old. She likes to lunch in warm shallow sandy waters with easy access to food such as a seaweed salad.

The outside of the shell is in the shape of an elegant cone, which has a distinctive spiral of spines arranged in bands that become wider towards the opening of the shell. Between the shell and the mantle, the part of the mollusc that forms the shell, Queen Conch can also be found very occasionally to be safeguarding a small, precious pearl.

If you are familiar with the lustrous metallic shine of pearls that are produced in a nacre-producing mollusc, the appearance of a conch pearl is quite different. The pearl produced by a conch is a calcareous concretion composed of calcite and may exhibit a beautiful flame-like pattern on its surface. The colour of a conch pearl can also be a subtle pink, orange, brown, or white.

Conch pearls are usually just 2 to 3 millimetres in size, but it is possible to find baroque or oval shaped pearls of up to 3 centimetres. Round shaped conch pearls are almost never discovered today. As finding a natural conch pearl is rare and highly valued, Queen Conch pearls are relatively unknown to the jewellery buying public. It is particularly difficult to find conch pearls that can be matched for use in sets or earrings.

For years populations of conch in the Caribbean have been dramatically reduced by over-fishing, poaching and pollution. Today in most countries fishing and diving for Queen Conch is banned, but her future reign sadly remains a difficult one.