The Speed and Style of the Ocean Liners

This spring, the V&A Museum in London celebrates the magnificence of the legendary Ocean Liners. Symbols of the technological advancement and celebration of luxury that defined the early 20th century, the Ocean Liners also gained notoriety for tales of human tragedy.

The exhibition takes its audience on a journey from the Belle Epoque to Art Deco, illustrating the way in which these monumental feats of engineering facilitated waves of entrepreneurship and the global movement of wealth during these periods.

The era was defined by its innovation, glamour and audacity, providing a canvas for highly crafted, extravagant interiors and for the ostentatious glamour of their upper class travelers.

Image 1: Duke and Duchess of Windsor's luggage, Goyard, about 1950

Image 2: Paquebot, Paris, Charles Demuth, United States 1921-22

The exhibition showcases objects from the emotive deckchairs of the downed Titanic, to the iconic graphics that the industry supported, the legendary luggage of Goyard and glittering flapper dresses of the 1920s.

The Cartier Tiara

One of the most famous jewels displayed in this current exhibition is the Allen Tiara, commissioned from the legendary house of Cartier in 1909 by the Canadian banker and shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan, as a gift for his wife Marguerite.

As with the Ocean Liners themselves, Cartier’s graphic combination of platinum, white diamonds and pearls came to symbolise the jewellery fashions of this generation.

The Allen Tiara was designed as an open work band in the Greek key style, millegrain-set with round faceted diamonds, inside an outer border of natural pearls, and framing an old mine-cut diamond at the centre.

Image: Diamond and pearl tiara saved from the Lusitania, Cartier, Paris 1909

The Cartier diamond tiara was fatefully taken by Lady Allen on board the Lusitania, travelling from New York to Liverpool, where she was accompanied by two of her three daughters, Anna and Gwendolyn, two maids, and a host of luggage.

The Sinking of the Lusitania

Cunard’s Lusitania began operational service in 1907, the largest and certainly one of the fastest ocean liners crossing the North Atlantic. Although the Lusitania was considered for requisition by the British Government at the start of the First World War, the liner was ruled out due to the immense quantities of coal that such a large ship would consume, at a time when endurance rather than speed was becoming important.

The Lusitania continued to operate as a commercial liner, carrying thousands of passengers back and forth from Europe to America.

Early in 1915, Germany declared the sea around Britain to be a war zone. Although, the German Embassy placed a warning on an advertisement for the Lusitania’s May 1915 voyage that Lady Allen was destined to board, many felt that the ship’s speed made her safe.

Image 1: Marlene Dietrich onboard the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York, 21 December 1950

Image 2: Detail of silk georgette and glass beaded Salambo dress, Jeanne Lanvin, Paris 1925

Perhaps Sir Hugh Allen’s long family association with the shipping industry gave his wife the encouragement to continue with her voyage? It was to prove a tragic decision; Lady Allen lost both of the daughters as the Lusitania was struck by a German torpedo.

Sinking within 18 minutes, the liner’s celebrated speed was one of the very factors that contributed to the significant loss of life as many of the lifeboats were dragged under water - only 791 of the 1,989 who travelled that day survived. Heartbreakingly, the tiara itself was rescued from the wreckage by one of the Allen’s maids.

The Plant Mansion and Necklace

Pierre Cartier was symbolic of an era of global travel and international business. Establishing the American office of his father’s Parisian jewellery business on Fifth Avenue in 1908, it was from New York that he built the company into the legendary brand name that it is today.

Cartier’s current flagship store in the city was originally built in 1905 for Morton F Plant, a wealthy railroad magnate, by architect Robert W. Gibson. Morton Plant’s wife Maisie encountered Cartier in 1917, becoming enamoured by a double-strand necklace of 128 flawless natural pearls.

Image: Wooden wall panel from the Beauvais deluxe suite on the Île de France, 1927

Cartier offered her husband a trade—the $1 million rare necklace plus $100 for the 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue mansion which would become his new boutique. At the time of the deal, the Plant’s home was valued at $925,000.

The End of an Era

It was not to prove a good deal for the Plants. Only a few short years later, the value of Mrs Plant’s pearls would dramatically decrease. Across the seas in Japan, Kokichi Mikimoto began to take his cultured pearls beyond Tokyo to international markets. Mikimoto launched his first overseas store in London in 1915, transforming the market for pearls as we know it today.

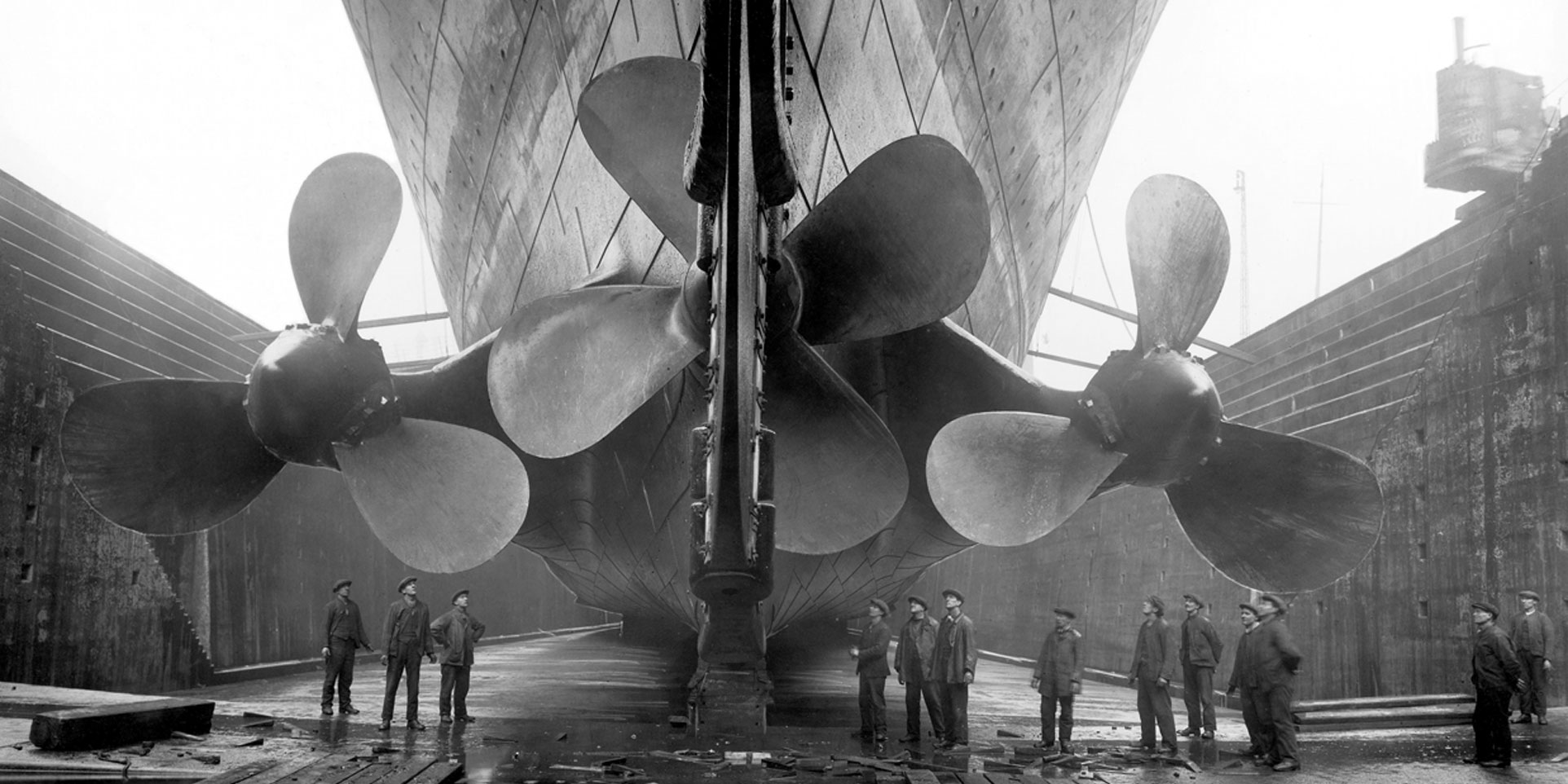

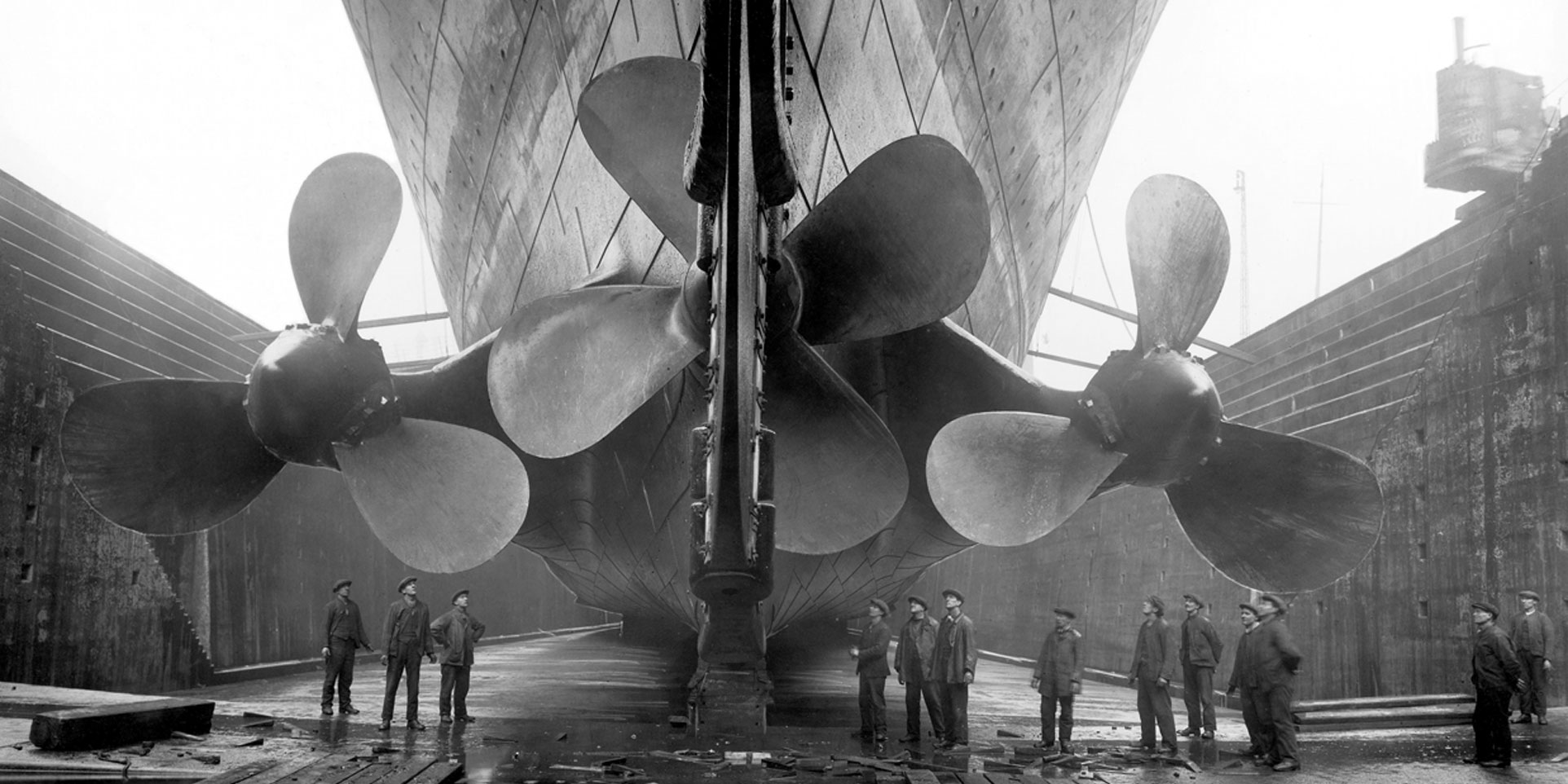

Image: Titanic in dry dock, c1911

As cultured pearl technology and farming overtook the natural pearl, and greatly broadened the market for these gems, so too would ocean travel for the super rich be superseded by the aeroplane. On 1st January 1914, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line became the world's first scheduled passenger airline service, marking the beginning of the end of the era of seaborne glamour.

An unique opportunity to revisit this sophisticated form of travel, the V&A exhibition 'Ocean Liners: Speed and Style' continues until 17th June 2018.

The exhibition takes its audience on a journey from the Belle Epoque to Art Deco, illustrating the way in which these monumental feats of engineering facilitated waves of entrepreneurship and the global movement of wealth during these periods.

The era was defined by its innovation, glamour and audacity, providing a canvas for highly crafted, extravagant interiors and for the ostentatious glamour of their upper class travelers.

Image 1: Duke and Duchess of Windsor's luggage, Goyard, about 1950

Image 2: Paquebot, Paris, Charles Demuth, United States 1921-22

The exhibition showcases objects from the emotive deckchairs of the downed Titanic, to the iconic graphics that the industry supported, the legendary luggage of Goyard and glittering flapper dresses of the 1920s.

The Cartier Tiara

One of the most famous jewels displayed in this current exhibition is the Allen Tiara, commissioned from the legendary house of Cartier in 1909 by the Canadian banker and shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan, as a gift for his wife Marguerite.

As with the Ocean Liners themselves, Cartier’s graphic combination of platinum, white diamonds and pearls came to symbolise the jewellery fashions of this generation.

The Allen Tiara was designed as an open work band in the Greek key style, millegrain-set with round faceted diamonds, inside an outer border of natural pearls, and framing an old mine-cut diamond at the centre.

Image: Diamond and pearl tiara saved from the Lusitania, Cartier, Paris 1909

The Cartier diamond tiara was fatefully taken by Lady Allen on board the Lusitania, travelling from New York to Liverpool, where she was accompanied by two of her three daughters, Anna and Gwendolyn, two maids, and a host of luggage.

The Sinking of the Lusitania

Cunard’s Lusitania began operational service in 1907, the largest and certainly one of the fastest ocean liners crossing the North Atlantic. Although the Lusitania was considered for requisition by the British Government at the start of the First World War, the liner was ruled out due to the immense quantities of coal that such a large ship would consume, at a time when endurance rather than speed was becoming important.

The Lusitania continued to operate as a commercial liner, carrying thousands of passengers back and forth from Europe to America.

Early in 1915, Germany declared the sea around Britain to be a war zone. Although, the German Embassy placed a warning on an advertisement for the Lusitania’s May 1915 voyage that Lady Allen was destined to board, many felt that the ship’s speed made her safe.

Image 1: Marlene Dietrich onboard the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York, 21 December 1950

Image 2: Detail of silk georgette and glass beaded Salambo dress, Jeanne Lanvin, Paris 1925

Perhaps Sir Hugh Allen’s long family association with the shipping industry gave his wife the encouragement to continue with her voyage? It was to prove a tragic decision; Lady Allen lost both of the daughters as the Lusitania was struck by a German torpedo.

Sinking within 18 minutes, the liner’s celebrated speed was one of the very factors that contributed to the significant loss of life as many of the lifeboats were dragged under water - only 791 of the 1,989 who travelled that day survived. Heartbreakingly, the tiara itself was rescued from the wreckage by one of the Allen’s maids.

The Plant Mansion and Necklace

Pierre Cartier was symbolic of an era of global travel and international business. Establishing the American office of his father’s Parisian jewellery business on Fifth Avenue in 1908, it was from New York that he built the company into the legendary brand name that it is today.

Cartier’s current flagship store in the city was originally built in 1905 for Morton F Plant, a wealthy railroad magnate, by architect Robert W. Gibson. Morton Plant’s wife Maisie encountered Cartier in 1917, becoming enamoured by a double-strand necklace of 128 flawless natural pearls.

Image: Wooden wall panel from the Beauvais deluxe suite on the Île de France, 1927

Cartier offered her husband a trade—the $1 million rare necklace plus $100 for the 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue mansion which would become his new boutique. At the time of the deal, the Plant’s home was valued at $925,000.

The End of an Era

It was not to prove a good deal for the Plants. Only a few short years later, the value of Mrs Plant’s pearls would dramatically decrease. Across the seas in Japan, Kokichi Mikimoto began to take his cultured pearls beyond Tokyo to international markets. Mikimoto launched his first overseas store in London in 1915, transforming the market for pearls as we know it today.

Image: Titanic in dry dock, c1911

As cultured pearl technology and farming overtook the natural pearl, and greatly broadened the market for these gems, so too would ocean travel for the super rich be superseded by the aeroplane. On 1st January 1914, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line became the world's first scheduled passenger airline service, marking the beginning of the end of the era of seaborne glamour.

An unique opportunity to revisit this sophisticated form of travel, the V&A exhibition 'Ocean Liners: Speed and Style' continues until 17th June 2018.

Image Credits:

Getty Imges