Tagged with 'History of pearls'

The very latest news, musings and opinions from the world of Winterson. Quite simply, a celebration of a jewellery, fashion, culture and the business behind luxury.

-

La Peregrina - Famous Pearl Jewels

La Peregrina - Famous Pearl Jewels

The legend of La Peregrina, one of the world’s most famous natural pearls, suggests that it was found in the mid-16th century near the island of Santa Margarita in the Gulf of Panama by an African slave, who was rewarded for his find with freedom.

At the time this extraordinary pear-shaped pearl was also one of the largest ever found, measuring approximately 17.5mm by 25.5mm and weighing over 11 grams before it was cleaned and drilled.

Don Pedro de Temez, the administrator of the Spanish colony, recognised the pearl's importance and brought it to Spain, where he gave it to the future king - Philip II of Spain. At this time the pearl began an incredible journey of ownership and it remains today one of the oldest and best documented historical jewels.

Philip presented with La Peregrina to Mary I of England, his future wife. Mary wore the pearl as a pendant suspended from a brooch, a jewel she can be seen wearing in a series of portraits from the period. After Mary’s death in 1558, the pearl was returned to the Spanish court where it remained for 250 years, and was worn by the wives of Kings Phillip III and IV.

Image 1: Mary Tudor, original artwork by Antonis Mor 1519-1575

Image 2: Elizabeth Taylor, c.1972

In 1808, when Napoleon installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain, the pearl found its way to France. In 1848 the pearl finally made its way to England into the Estate of James Hamilton, Duke of Abercorn. It was during this time it was given the name La Peregrina, which means the “Pilgrim” or “Wanderer”.

La Peregrina remains one of the largest perfectly symmetrical pear-shaped pearls in the world. The Hamiltons sold the pearl for $37,000 at Sotheby’s in 1969 to Richard Burton, as a Valentine Day's gift for Elizabeth Taylor.

It was the exquisite heirloom that sealed one of Hollywood's most tempestuous love stories. Drop and pear-shaped pearls are often made into pendants, but during its history La Peregrina was worn as a brooch, a pendant to a necklace, the centrepiece of a necklace and even a hat ornament. Taylor commissioned Al Durante of Cartier in 1972 to design a ruby and diamond necklace mount for the pearl. The complete piece is quite stunning and truly one of a kind.

When Taylor died, La Peregrina was sold at auction by Christies in 2011 to raise funds for the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, which was established by Taylor to help provide direct services throughout the world for people living with AIDS.

Christies estimated the value of La Peregrina to be between $2 million and $3 million, making Lot 12 the second highest valued lot of the auction. In a fitting tribute to the memory of Elizabeth Taylor, the auction of legendary jewels surpassed all expectations, with the sale of La Peregrina for $11,842,500 creating two new world auction records for a historic pearl and for a pearl jewel.

Where, we wonder, will the next stage of its historic journey be taking the Wanderer to? -

The Hope Pearl - Famous Pearl Jewels

The Hope Pearl - Famous Pearl Jewels

From time to time in The Journal, we explore the origins and stories around famous pearls and items of pearl jewellery. In this article, we continue to share our fascination for this most stunning of gemstones, with the extraordinary Hope Pearl.

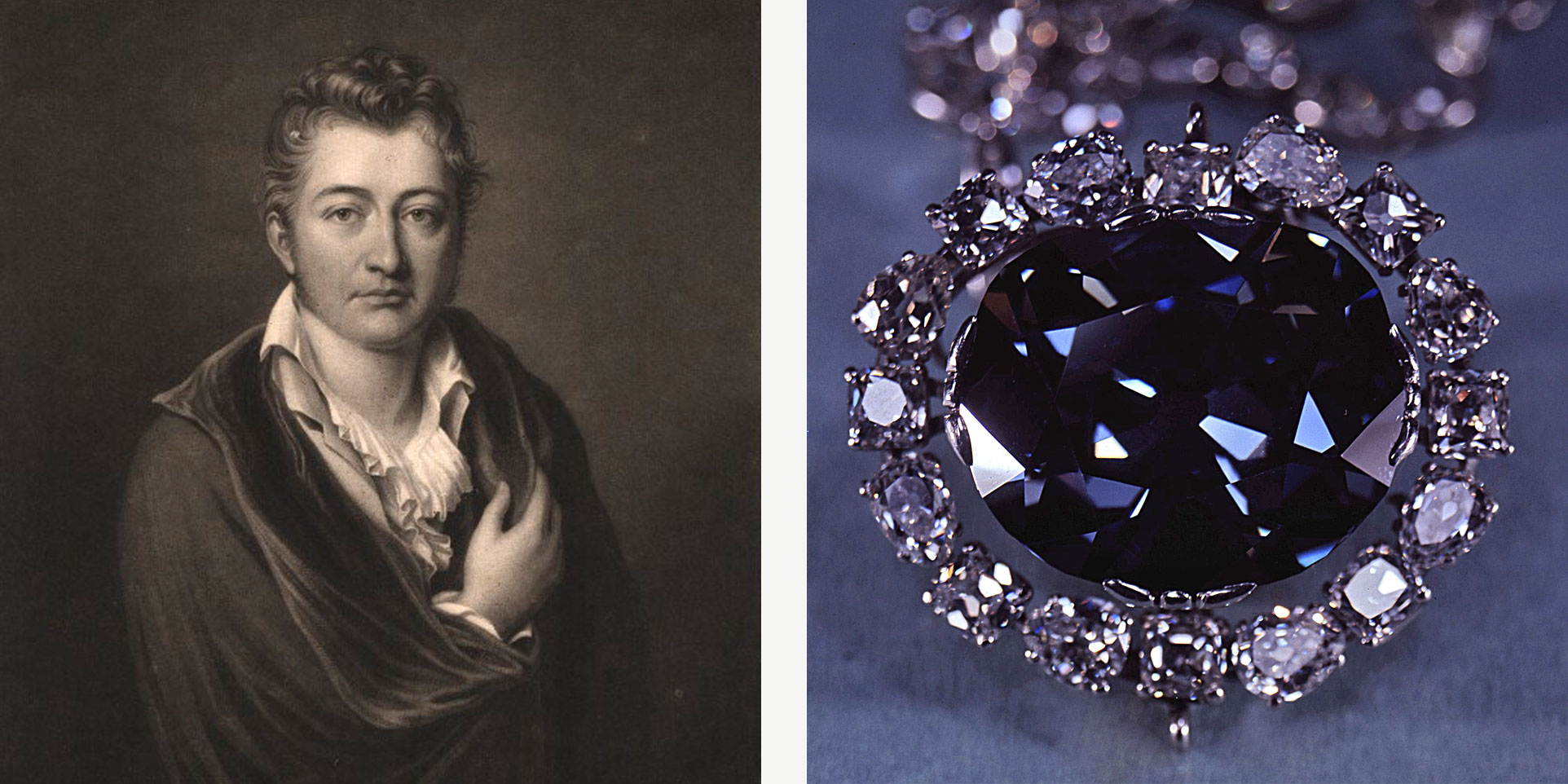

Believed at the time to be the largest natural saltwater pearl ever discovered, the Hope Pearl was named after its owner Henry Philip Hope. Hope (1774-1839) was an Anglo-Dutch gem collector, who acquired many renowned gemstones and diamonds for his collection, including the famous blue Hope Diamond and approximately 148 natural pearls of significant size.

Image 1: Henry Philip Hope, by Thomas Goff Lupton, after Bouton, 1823

Image 2: The Hope Diamond

The Hope Pearl was one of Henry Philip Hope’s first acquisitions as he set about building his collection of gems and jewellery. The Hope Pearl was believed to have been possibly acquired by Tavernier and sold to King Louis XIV in 1669, before being subsequently sold to Hope, around 1795. The pearl was included in a catalogue of his collection that was published by Bram Hertz in 1839, the year that Henry Philip Hope died.

Its exact origin is unknown, but it is likely, given the period when it was discovered, that the Hope Pearl was an ‘oriental’ pearl. It was perhaps found in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea or the Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka, which were the traditional centres of the pearl fishing industry for over 4,000 years.

Weighing around 1,800 grains (or 450 carats), the Hope Pearl is a blister pearl. The pearl would have formed on the inner surface of the mollusk's shell. This location is still visible on the surface of the gem, although it has been polished to resemble other parts of the pearl’s surface.

It is its size and cylindrical drop shape that makes this pearl so unusual. Natural blister pearls are thought to form as pearls within the mollusk's mantle tissue, before breaking free and being pressed into the shell. Cultured blister pearls today are usually hemispherical, with a layer of mother of pearl being used to create the flat back of a mabe pearl.

Measuring approximately two inches by four inches, and ranging in colour from greenish-gold on one end to white on the other, the Hope Pearl contributed significantly to an explosion of interest in baroque pearls and baroque pearl jewellery in the late 16th to 17th centuries.

The popularity of baroque pearls stemmed from their unique qualities of shape and colour, with master jewellers creating extraordinary gems in forms that the pearls themselves suggested. The Swan Pendant, now at the Hermitage State Museum in St Petersburg, and The Canning Jewel, part of the Victoria & Albert Collection, are two of the most famous examples.

Hope had the pearl mounted in a pendant setting in the shape of a crown, and featuring rubies and diamonds. Now in private ownership, the Hope Pearl has been exhibited internationally including at the Natural History Museum in London and the Smithsonian in New York. -

The Speed and Style of the Ocean Liners

The Speed and Style of the Ocean Liners

This spring, the V&A Museum in London celebrates the magnificence of the legendary Ocean Liners. Symbols of the technological advancement and celebration of luxury that defined the early 20th century, the Ocean Liners also gained notoriety for tales of human tragedy.

The exhibition takes its audience on a journey from the Belle Epoque to Art Deco, illustrating the way in which these monumental feats of engineering facilitated waves of entrepreneurship and the global movement of wealth during these periods.

The era was defined by its innovation, glamour and audacity, providing a canvas for highly crafted, extravagant interiors and for the ostentatious glamour of their upper class travelers.

Image 1: Duke and Duchess of Windsor's luggage, Goyard, about 1950

Image 2: Paquebot, Paris, Charles Demuth, United States 1921-22

The exhibition showcases objects from the emotive deckchairs of the downed Titanic, to the iconic graphics that the industry supported, the legendary luggage of Goyard and glittering flapper dresses of the 1920s.

The Cartier Tiara

One of the most famous jewels displayed in this current exhibition is the Allen Tiara, commissioned from the legendary house of Cartier in 1909 by the Canadian banker and shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan, as a gift for his wife Marguerite.

As with the Ocean Liners themselves, Cartier’s graphic combination of platinum, white diamonds and pearls came to symbolise the jewellery fashions of this generation.

The Allen Tiara was designed as an open work band in the Greek key style, millegrain-set with round faceted diamonds, inside an outer border of natural pearls, and framing an old mine-cut diamond at the centre.

Image: Diamond and pearl tiara saved from the Lusitania, Cartier, Paris 1909

The Cartier diamond tiara was fatefully taken by Lady Allen on board the Lusitania, travelling from New York to Liverpool, where she was accompanied by two of her three daughters, Anna and Gwendolyn, two maids, and a host of luggage.

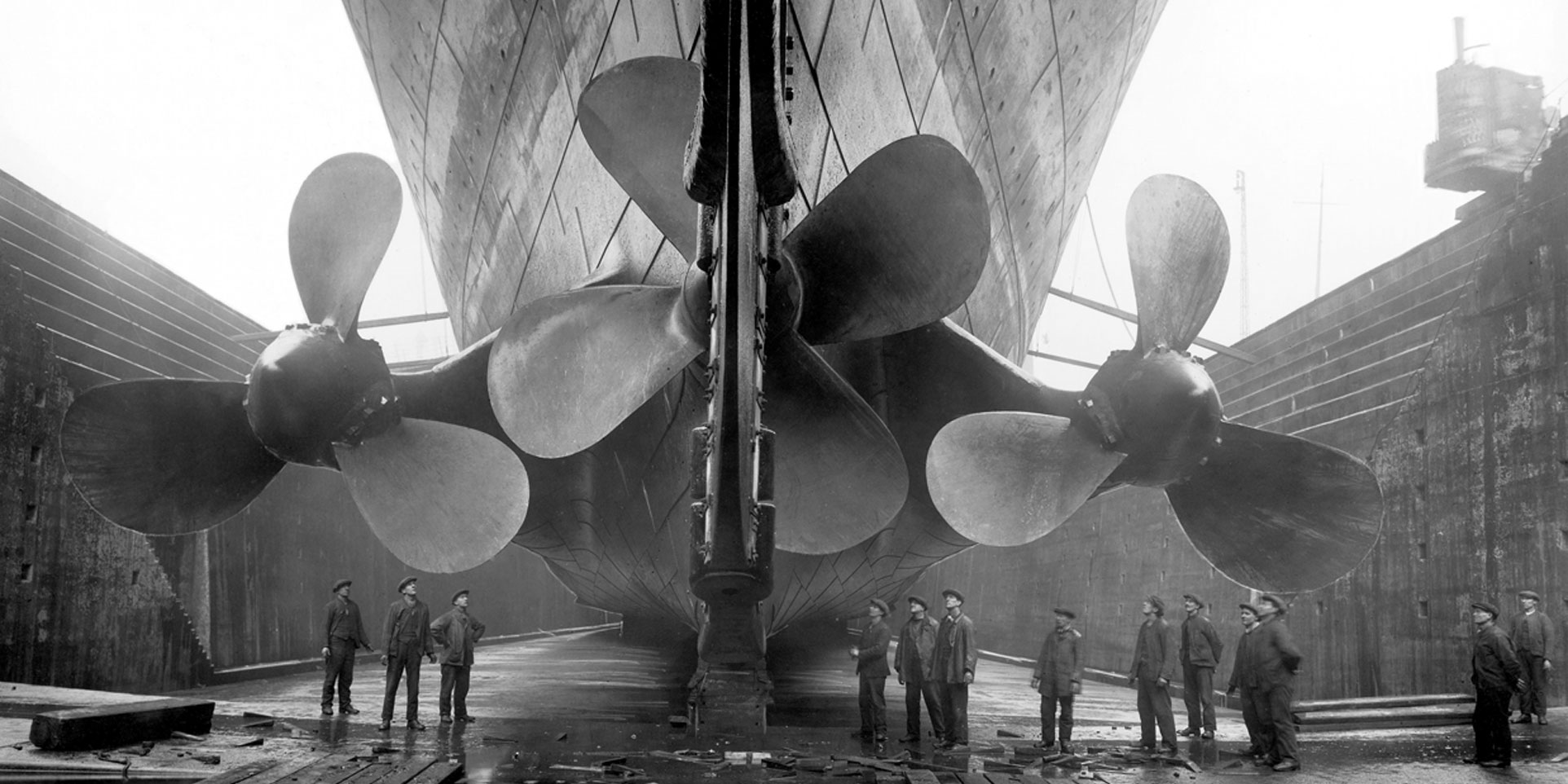

The Sinking of the Lusitania

Cunard’s Lusitania began operational service in 1907, the largest and certainly one of the fastest ocean liners crossing the North Atlantic. Although the Lusitania was considered for requisition by the British Government at the start of the First World War, the liner was ruled out due to the immense quantities of coal that such a large ship would consume, at a time when endurance rather than speed was becoming important.

The Lusitania continued to operate as a commercial liner, carrying thousands of passengers back and forth from Europe to America.

Early in 1915, Germany declared the sea around Britain to be a war zone. Although, the German Embassy placed a warning on an advertisement for the Lusitania’s May 1915 voyage that Lady Allen was destined to board, many felt that the ship’s speed made her safe.

Image 1: Marlene Dietrich onboard the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York, 21 December 1950

Image 2: Detail of silk georgette and glass beaded Salambo dress, Jeanne Lanvin, Paris 1925

Perhaps Sir Hugh Allen’s long family association with the shipping industry gave his wife the encouragement to continue with her voyage? It was to prove a tragic decision; Lady Allen lost both of the daughters as the Lusitania was struck by a German torpedo.

Sinking within 18 minutes, the liner’s celebrated speed was one of the very factors that contributed to the significant loss of life as many of the lifeboats were dragged under water - only 791 of the 1,989 who travelled that day survived. Heartbreakingly, the tiara itself was rescued from the wreckage by one of the Allen’s maids.

The Plant Mansion and Necklace

Pierre Cartier was symbolic of an era of global travel and international business. Establishing the American office of his father’s Parisian jewellery business on Fifth Avenue in 1908, it was from New York that he built the company into the legendary brand name that it is today.

Cartier’s current flagship store in the city was originally built in 1905 for Morton F Plant, a wealthy railroad magnate, by architect Robert W. Gibson. Morton Plant’s wife Maisie encountered Cartier in 1917, becoming enamoured by a double-strand necklace of 128 flawless natural pearls.

Image: Wooden wall panel from the Beauvais deluxe suite on the Île de France, 1927

Cartier offered her husband a trade—the $1 million rare necklace plus $100 for the 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue mansion which would become his new boutique. At the time of the deal, the Plant’s home was valued at $925,000.

The End of an Era

It was not to prove a good deal for the Plants. Only a few short years later, the value of Mrs Plant’s pearls would dramatically decrease. Across the seas in Japan, Kokichi Mikimoto began to take his cultured pearls beyond Tokyo to international markets. Mikimoto launched his first overseas store in London in 1915, transforming the market for pearls as we know it today.

Image: Titanic in dry dock, c1911

As cultured pearl technology and farming overtook the natural pearl, and greatly broadened the market for these gems, so too would ocean travel for the super rich be superseded by the aeroplane. On 1st January 1914, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line became the world's first scheduled passenger airline service, marking the beginning of the end of the era of seaborne glamour.

An unique opportunity to revisit this sophisticated form of travel, the V&A exhibition 'Ocean Liners: Speed and Style' continues until 17th June 2018. -

What are the classic jewellery designs for pearls?

What are the classic jewellery designs for pearls?

It has long been known that the pearl has played a central role in jewellery, with some of the earliest recorded fragments of a pearl necklace being dated to the 4th century BC. What are the most popular and successful designs of classic jewellery that pearls have been used with - and how are they being updated today?

The pearl was believed by numerous cultures to symbolize purity and to offer protection, as well as being indicative of their owner’s social position. Their beauty and rarity meant that the gems held an almost mythological, and certainly significant financial status.

The Timeless Classic

There are many examples through the ages of how our love for the pearl has influenced the wearing, adornment and design of the classic jewellery that we love today.

In China as early as 2300 BC, pearls were considered appropriate gifts for royalty, representing not just the integrity and loyalty of the giver but also the wisdom and virtue of the wearer. Julius Caesar passed a law in the 1st century BC, which determined that pearls should only be worn by the ruling classes.

In India, it is still believed that the pearl confers calm on its wearer, attracting wealth and good luck. The gem was a favourite of Indian royalty, most notably the Mahraja Khande Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, whose seven-strand necklace was legendary even within a culture where extraordinary gems were plentiful – so much so that the famed necklace gained a name of its own: the Baroda Pearls.

Image: A Winterson South Sea pearl and pave diamond clasp necklace

Their extravagant value lead to the pearl playing an important role in trade, which only increased once they were discovered in Central and South America in the 15th century, a discovery which led to the so called Pearl Age.

As a visible symbol of wealth, the demand for pearls escalated, particularly in Western Europe, where royals and aristocrats increasingly emulated their peers in China, India and the Arab states, commissioning elaborate pearl necklaces, earrings, bracelets and brooches.

By the 19th century, demand for pearl jewellery was so high that the supply of natural pearls began to dwindle to the point today where historic pieces of natural pearl jewellery are so rare they can fetch high six or seven figure sums at auction.

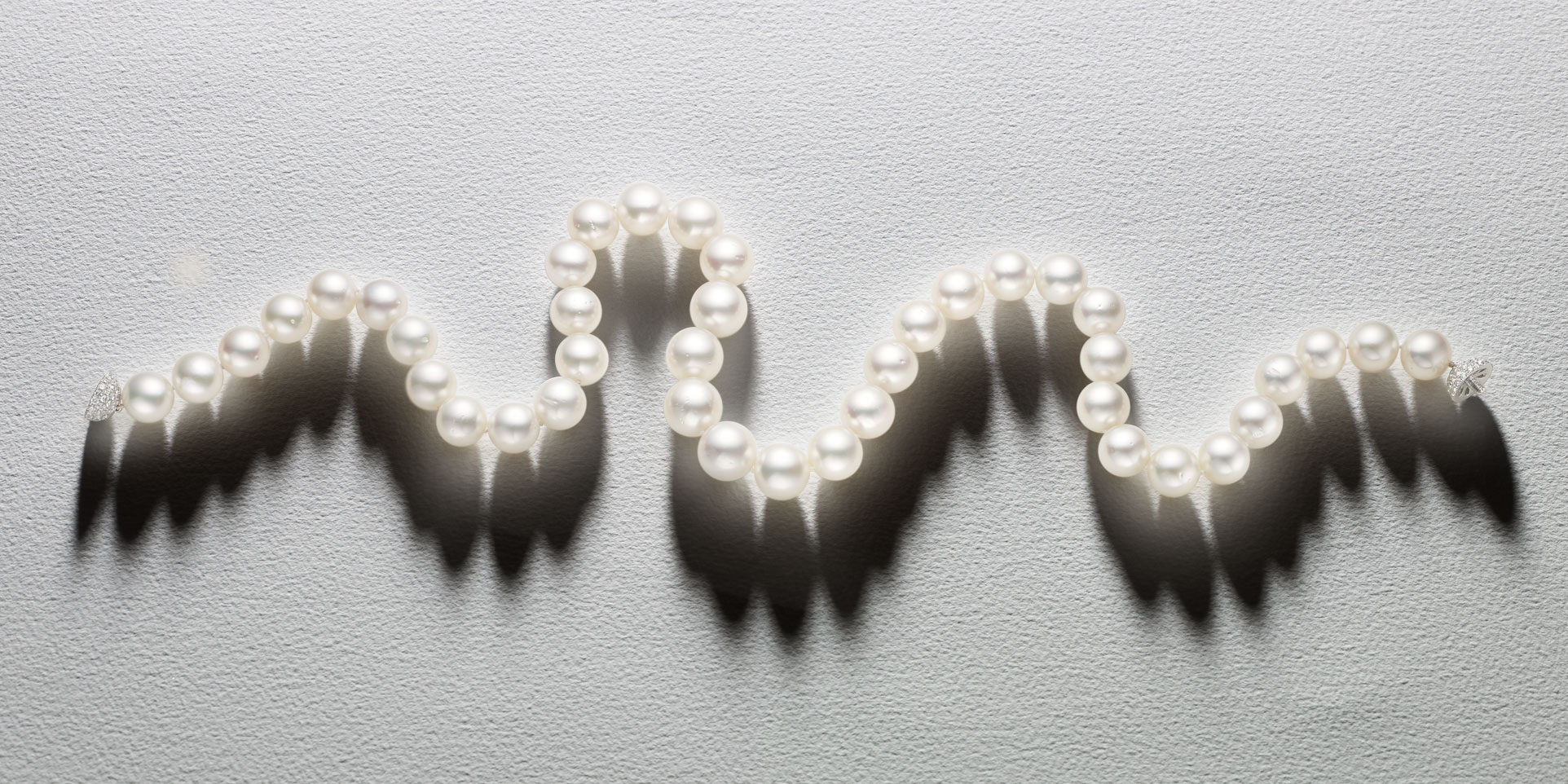

The Pearl Necklace

As a result of the way that they reflect light to the face, strands of pearls have become the most popular form of classic jewellery over the ages. The more strands in a necklace, the greater that the necklace reflected the wealth of its owner.

Image 1: Blush Sunrise Necklace

Image 2: A portrait miniature of Emma Ostaszewska née Countess Załuska, ca. 1850s

The lustre of the gems was often preserved by having Victorian maids wear the necklaces during the day to keep the pearls warm and radiant for their mistresses.

With the arrival of the cultured pearl, the status of the gem has shifted over the 20th century, becoming more widely accessible. The multi strand pearl necklace remains an enduring piece of classic jewellery that actresses, society ladies, designers and jewelers such as Winterson prize winner Bella Mung continue to revisit.

Our pearl specialists individually select and grade each strand that makes up a Winterson necklace, often viewing and reviewing pearls throughout the day to be aware of the impact of shifting light on the overtones and lustre of the pearl. Our necklaces are available in multiple lengths, colours, and different types of pearls, including Akoya, Freshwater, South Sea and Tahitian. Read our Buying Guide to choosing a necklace to learn more.

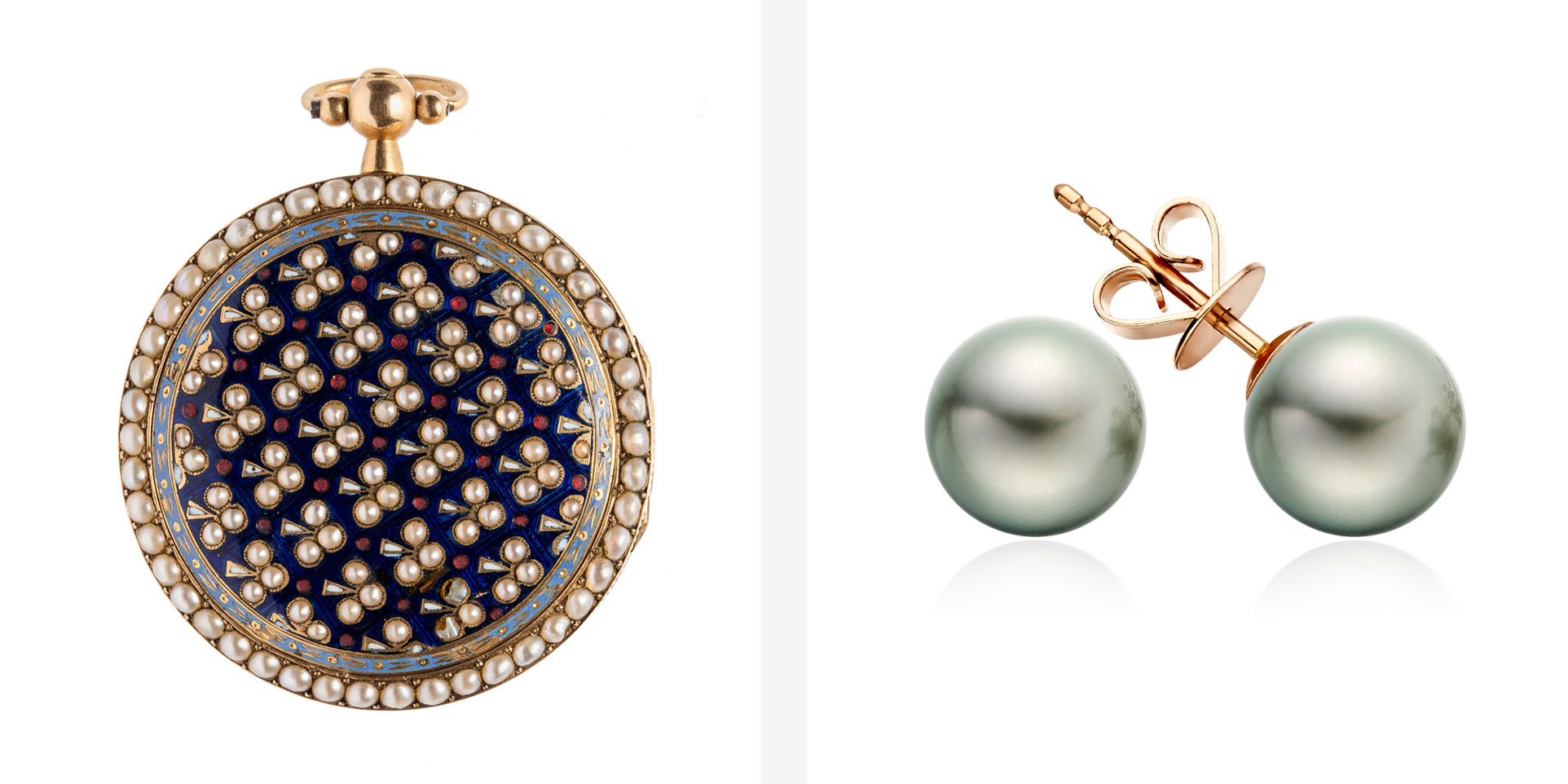

The Pearl Stud

After the pearl necklace, pearl studs form another cornerstone of a woman’s classic jewellery wardrobe. The legendary Coco Chanel was well known for her enduring love of these beautiful gems,which she wore prodigiously (real and fake together).

Although she favoured the monochrome white pearl necklace, once famously declaring “a woman needs ropes and ropes of pearls", her single pearl clip earrings were almost as significant a part of her iconic image.

Image 1: Pocket watch of gold, with enamel and oriental pearls, 1800

Image 2: Green Grey Tahitian Pearl Stud Earrings in Rose Gold

The pearl studs at Winterson are available in a wide choice of colours, sizes from 6-12mm , types of pearls and finished with 18 carat white, yellow and rose gold earring posts and butterflies.

The Pearl Drop Earring

In an era where natural pearls, with all their unique forms and qualities, were the stones that were used in classic jewellery, the popularity of the drop shape is unsurprising. Vermeer’s famous Girl with a Pearl Earring provides the archetypal blueprint for the freshwater drop earring, a classic style that has most recently been adopted by the current Duchess of Cambridge.

Image 1: Yellow Gold Diamond Leverback And Freshwater Pearl Drop Earrings

Image 2: The Girl With The Pearl Earring, Johannes Vermeer, 1665

Natural pearl drops continue to fetch high sums at auction, as the sale of a pair of earrings owned by Empress Eugenie of France, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, amply demonstrated. Fetching $3.3 million, the drops were then promptly reset for their new owners by American high jeweler Lee Sieglson, reflecting that the value was paid for the pearls rather than their original setting.

The Seed Pearl Ring

Seed pearls gained popularity in Georgian and Victorian jewellery, where they often accented the frame of rings and earrings in the same way that diamond pave does today.

Image 1: Funeral Ring, Landscape and Temples, 18th Century

Image 2: Beau Seed Pearl and Enamel Ring with Yellow Gold

Often seen as part of mourning jewellery, set around painted portraits or landscapes or offset by washes of enamel, this era of jewellery formed the basis of inspiration for Alice Cicolini’s Beau collection for Winterson.

The Pearl Brooch

Seed pearl pave, where lines of these wonderful tiny pearls are set in single or multiple rows, also offered a stylish way for jewellers to incorporate the pearl in brooches. This form of jewellery became highly popular in the 19th century as a decorative jewel, rather than as a functional object which was the original purpose of the brooch.

Although their popularity has waxed and waned over the years, it appears as if the brooch may be increasing in popularity again as fashion brands and jewellers alike seek new surfaces for jewels to come alive.

Perhaps pearls may also find their way onto these new generation designs. The Duchess of Cambridge might have recently signalled the reinvention of this classic jewellery design at a recent state visit, wearing the Queen’s triple pearl and diamond leaf pearl brooch with the stunning Collingwood Pearl and Diamond drop earrings which she often favours. -

Bejewelled Treasures from the Al Thani Collection

Bejewelled Treasures from the Al Thani Collection

Winterson's Creative Director Alice Cicolini takes a retrospective glance at the celebrated Al Thani collection of jewellery. The exhibition, which first appeared in Bejewelled Treasures at London's Victoria & Albert Museum, is set to open this Spring at the Grand Palais, Paris in March 2017.

The Al Thani Collection is a unique collection of jewels from an unusually broad chronological period that spans the Mughal period of the early 1600s to the present day. With such a diverse group of objects to select from, the V&A exhibition's curator Susan Stronge paints an impressive, if partial, picture of the development of Indian jewellery techniques and tastes.

Jewellery in Mughal society

The focus in the early part of the exhibition emphasises the almost ubiquitous presence of gemstones and jewellery throughout the Mughal court: from fly whisks and wine cups, to backscratchers and huqqa bases. The prevalence of precious and semi-precious gems led visitors to India in this period to remark on the magnificence of courtly life, its gem-encrusted thrones and imperial bodies that sparkled with jewels.

Hindu rulers lived under clear instruction as to the importance of establishing of an almost God-like regal body politic, through dress, jewellery and grooming. This remarkable profusion of jewellery, which their Mughal successors appeared to share, went far beyond the ruling classes to encompass men and women at all levels of society.

Image 1: Spinel and pearl necklace

Image 2: Silk sword sash with jewelled gold fittings

This is very revealing of the important role that jewellery played, not simply in the creation of status, but in what modern historian Daud Ali has described as “the spiritual and literary life of Indian societies” and the “association of jewels with light, virtue and beauty”. It is in early Sanskrit texts such as the arthashastra and brihatsamhita that the spiritual, cultural and healing values of stones, grading & assessment and jewellery techniques began to be established.

A love for pearls and gems

Many of these central tenets of gemlore still inform contemporary Indian jewellery making and buying practice, today with the navratna, or nine-stones, continuing to play a alismanic role in jewellery culture. Of these, the five great stones, or mahararatnani, - diamond, pearl, ruby, sapphire and emerald - dominate Indian jewellery culture as they did several hundred years ago.

As a result, for pearl lovers the Bejewelled Treasure exhibition offers a wealth of extremely fine examples. Visitors to India frequently remarked on the ropes of pearls that covered the bodies of both men and women, rulers and lesser subjects alike, upon which it would have been difficult to place a price. The arthashastra particularly notes methods for grading pearls, and the types of necklaces into which they could be strung, including one gravity-defying necklace of 1,008 rows.

It may be that one of the reasons that visitors saw pearls worn by non-royal courtiers was that, much like their British equivalents, Indian rulers charged their servants with wearing their pearls during the day to keep them both warm and luminous. Although the geographical proximity to the pearl fishers of the Arabian Gulf and Sri Lanka would have given Indian rulers greater access to pearls than some of their European peers, the pearl was still regarded a symbol of status. Some rulers were believed to drink powdered pearls as an aphrodisiac, and the Sanskrit word for pearl, manjari, means “bud” denoting the sensuality the gem has come to symbolise.

Image 1: Diamond turban jewel made for the Maharaja of Nawanagar

Image 2: Cartier Brooch set with emeralds, sapphires and diamonds

Other notable aspects of the exhibition include several exquisite examples of spinel, a stone which has long been celebrated in the subcontinent whilst remaining relatively unknown in the West. A combination of increasing scarcity, the price of tourmaline, the prevalence in the market of glass-filled and heat treated ruby and the spinel’s relatively low profile, however, marks this gemstone out as a major jewellery trend.

One of the main centerpieces of the show, and one of the few pieces in the exhibition not from the Al Thani Collection, is the Timur Ruby, rather abstractly titled since it is neither a ruby nor was it ever owned by the famous Indian ruler. Now part of the collection of Queen Elizabeth II, the stone was given to Queen Victoria by the East India Company in 1851, and then set in gold, enamel and diamonds by Garrards in 1853. The gem itself demonstrates the significant value placed on these stones by a succession of Mughal rulers, engraved as it is with the names of five royal owners from Jahangir, son of Akbar, in 1612 to Sultan Nadir in 1741.

Contrasting traditional with modern

The Timur Ruby also demonstrates the differing understanding of value that remains central to much of India’s more traditional jewellery making practice. Unlike Western cultures, where brilliance, fire and perfect precision cutting constitute extraordinary gems, the Indian subcontinent holds true (in its more traditional manifestation) to the notion that a stone’s natural character and form – its scale, luminance, colour and clarity – are what defines its beauty.

One of the main techniques that the exhibition focuses on is kundan, the practice of using highly refined gold to set natural, irregular stone shapes within fine, symmetric settings. Its aesthetic is one that has come to define traditional Indian jewellery, and its abandonment by India’s contemporary high jewellers is one of the most notable characteristics of their perceived modernity.

It is the quite clear break with traditional jewellery making practice that the exhibition makes visible, which is one of the show’s most interesting features. Alongside the rejection of traditional setting techniques, it is the widespread preference for platinum (with yellow gold removed to the reverse or interior structure of these new jewels) that has seemed to define “modernity” in contemporary Indian jewellery.

Western influences

Certainly this trend is most evident within the fertile Art Deco period that saw such a volume of commissions from Indian rulers to luxury high jewellery houses in the West such as Cartier, Boucheron, and more recently JAR, and more recently in contemporary jewellery from India itself.

Image: Gold and diamond hair ornament

Stronge implies that the increased cross-fertilisation with Western tastes has resulted in a loss of regional difference across Indian jewellery, although it's perhaps difficult to conclude about a wider trend from the prism of a very personal selection of objects. It is certainly true that the contemporary jewelers that Al Thani has favoured lean very heavily towards the language of Westernised Indian-ness that Cartier, his Indian clients, and the many other 1920s Western jewellery houses who operated in the country, helped to establish.

The exhibition catalogue relates a lovely vignette of Jacques Cartier’s first visit to India as part of the Delhi Durbar of 1911, marking the coronation of George V as Emperor of India. Cartier had brought, Stronge relates, a selection of jewellery for women, but rapidly realized “the enormous potential of this market was that the princes bought mostly for themselves”.

The legacy of the Al Thani treasures

Perhaps what makes this exhibition so unique in its presentations of high jewellery is that the majority of the pieces chosen have been created to be worn or used by men rather than women, and this in itself is something worth visiting for.

As masculine jewellery cultures diminish so dramatically across the world, the exhibition profiles a dying way of life – both that of the makers, as their traditional arts appear to fade from fashion, and the wearers, and ways of wearing, that these extraordinary gems represent. -

Mystery Surrounds The Cheapside Hoard

Mystery Surrounds The Cheapside Hoard

Mystery still surrounds the jewels of the Cheapside Hoard. Why were these striking jewels originally buried deep beneath the cellar of a building in London's Cheapside and what was the purpose of many of the objects that the Hoard contained?

The Cheapside Hoard was discovered in 1912, the most significant find of its kind, during the redevelopment of Cheapside, a medieval street between modern day St. Paul's Cathedral and Bank. This bustling market route was famously described by Charles Dickens Jr. as "the greatest thoroughfare in the City of London".

The exhibition's curators can be relatively accurate about the date that the Cheapside Hoard was originally buried. The particular style of the jewels and the date of the Great Fire of London that flattened much of the area around Cheapside, bookends the Hoard being buried during a decade that was approximately between 1650-1666.

Given the repetition of a number of similar styles and ideas throughout the collection - numerous carved grapes in amethyst and emerald, ropes of enamelled floral chains - it does seem that the owner might have been a jeweller or dealer, perhaps from nearby Goldsmiths' Row. The Hoard clearly pinpoints the fashions of the day in a way that the collection of an individual might not.

Currently on show at the Museum of London in its entirety for the first time in a century, there are just a few pearls in the Hoard that have survived the four hundred years since the pieces were first hidden away. The myriad empty settings that remain - the curators estimate approximately 1,386 were intended for pearls - are testament to the gem's enduring appeal.

Of those on display, the pieces crafted from fine gold wirework, encasing sheets of back-to-back mother of pearl (most now sadly lost), are captivating. Designed in the shape of what the curators describe as "the translucent seed pods of the plant Lunaria, regarded as a symbol of honesty and appreciated for its healing properties," it is not clear that the items were ever intended for wear.

Mother of pearl was more commonly found in inlay work at this time, and the scale of the pieces precludes them being worn as earrings. However, the enamelled four-petalled cross that links the fifth drop to the main four petals would have given the gems a lovely movement, and had the mother of pearl itself been engraved, as the curators suggest the material often was, these pieces would have been quite beguiling.

The combination of enamel and seed pearls (a chain of which in the Hoard has settings for over 500 pearls with only 7 remaining) was popular in London at this time, a trend which Winterson's Beau collection designed by Alice Cicolini in some part echoes.

Seed pearls also appear on delicate wirework buttons that would have required a high level of craftsmanship for these to be realised.

Of the striking pearls of the Cheapside Hoard that have survived the centuries, the most notable are a baroque pearl carved into the shape of a ship, complete with wirework mast and rigging, and an 11mm pearl with a deep "orient lustre" that sits above a figuratively carved sapphire.

As with many other gems, a pearl of "oriental origin" commanded a high price during the period, the term being used to imply quality as much as provenance. Londoners in the 1600s, the curators believe, were particularly fussy about the quality of their pearls, with even high grade pearls going unsold if they were not of the correct colour and radiant lustre.

At Winterson, where great care is also taken to identify the finest quality pearls to make up our jewellery, we tend to agree!

The Cheapside Hoard: London's Lost Jewels is exhibiting at the Museum of London until 27th April.

-

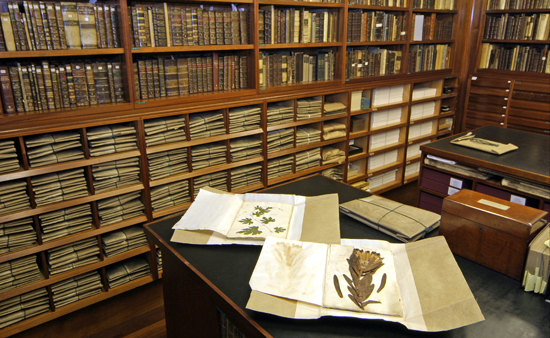

A Peek at the Pearls of Carl Linnaeus

A Peek at the Pearls of Carl Linnaeus

The world of pearls can hold many surprises, but it is not everyday that you have an opportunity to view a historic treasure secured safely beneath the streets of London.

The experimental pearls of famed Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus are about to join the forthcoming Pearls Exhibition at the V&A and so we jumped at the chance to see these early successful attempts to culture a spherical pearl in close up.

CARL LINNAEUS

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) is best known for his method of classifying organisms that uses two latin names to represent the genus and the species, for example 'Homo Sapiens'. This taxonomy is conventionally used today to describe and classify the hierarchical relationships of animals, plants and insects to each other.

Linnaeus' collections of specimen organisms, including dried flowers, insects, fish and molluscs are unique and are still a primary reference point for scientists to determine if they have found a new species.

Following his death, the Linnean collections were purchased by Sir James Edward Smith in 1784 and transported to London, where they remain today.

THE LINNEAN SOCIETY

In 1788, Smith also founded The Linnean Society to provide a forum to discuss and promote the study of natural history.

The Linnean Society is the world's oldest active biological society. It was at a meeting of the Society in 1858 that papers by Charles Darwin were presented outlining the theory of natural selection and evolution.

The collections were obtained by the Society in 1829 and are today securely held in a vault below the courtyard of Burlington House, Piccadilly in central London. Leather bound books, old parchment folders and specimen trays line the carefully curated shelves and drawers.

Also in the strongroom was a very rare (and valuable) signed first edition of Charles Darwin's 'Origin of the Species' - a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see.

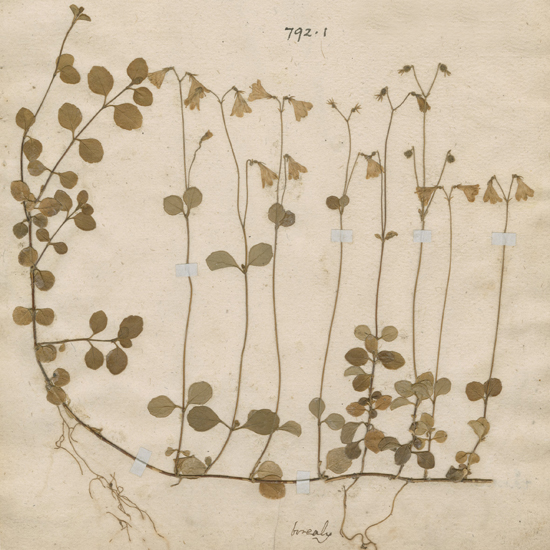

LINNAEA BOREALIS

Carefully wrapped in parchment was this original specimen of Linnaea Borealis, a wildflower of northern and alpine origin that has a distinctive double twin flower shape. The flower is named after Linnaeus as it was a favourite of his whilst travelling in Lapland.

As well as having a beautiful white pink flower, Carl Linnaeus fell in love with the wildflower for the way that it grew persistently in the undergrowth and its ephemeral, short-lived life. These were two symbols that he felt were important in his own life and portraits of Linnaeus, including the one above, and in the Society all feature the Linnaea Borealis.

This little flower has a special meaning for Winterson as it was an inspiration for our own flower motif, also honouring its link with Linnaeus and his early achievements in culturing pearls.

LINNAEUS AND PEARLS

Linnaeus declared in 1761 that 'he had heard of people who made gold, but had never heard of any who could make pearls'. Describing the lengthy and time-consuming efforts to find natural pearls that he had seen in Purkijaur, Lapland, Linnaeus believed that a technique for culturing pearls existed that would be more effective and profitable for Sweden.

Linnaeus started to experiment with 'Unio Pictorum', a species of freshwater mussel called the Painter's mussel. This mussel was named as traditionally its shells were used by painters as convenient receptacles for mixing paint.

His technique was a variation of an old Chinese method for producing blister pearls. Drilling a hole in the mussel's shell, Linnaeus inserted a small granule of limestone between the mantle and the shell to help produce a free spherical pearl inside the mussel.

The mussels were returned to the riverbed for six years to produce what is regarded as the world's first spherical cultured pearls. They are indeed historic and fascinating to view.

Linnaeus' method is also based on an old misunderstanding that pearls are created with a grain of sand. We know now that a response to illness or a parasite is the more likely explanation for the growth of natural pearls in an oyster or mussel.

These experimental pearls were not ultimately the source of riches that Linnaeus had hoped for, but he was enobled by the King of Sweden for his efforts taking the title von Linné. The pearls, a patent and Linnaeus' secret were sold to a Swedish merchant named Peter Bagge, but nothing came out of this venture.

Another Londoner Sir John Hunter is recorded as having attempted to culture freshwater pearls in his ponds at Earl's Court Manor House using a similar method to Linnaeus, but it was left to a different Englishman William Saville-Kent to make the next break-through in pearl culturing.

SEE THE LINNAEUS PEARLS AT THE V&A

We would to like thank Elaine Charwat, Deputy Librarian of the Linnean Society for her fabulous help in showing us Carl Linnaeus' pearls.

The pearls themselves are on display soon at Pearls, the V&A's new exhibition. Not to be missed...

-

Pearls Exhibition at the V&A Museum

Pearls Exhibition at the V&A Museum

With much excitement and anticipation, the Pearls exhibition at the V&A Museum opens later this month in London.

PEARLS EXHIBITION AT THE V&A

Promising to be one of the biggest Autumn shows, the exhibition will show off the luxurious qualities of some of the world's most unusual and valuable pearls and jewellery, as well as exploring the unique heritage and impact on popular culture of this beautiful gem.

We are very fortunate to be able to ask Beatriz Chadour-Sampson and Hubert Bari, the curators of the Pearls exhibition, about the show and what a visitor can look forward to. We would like to thank them, the V&A and the Qatar Museums Authority for their support with this article.

Here are Beatriz and Hubert's thoughts on 'Pearls'.

How special has this exhibition been for you and to curate? What did you hope that its visitors may learn about pearls?

From all gems, it is the most unusual as the natural pearl is produced by living animals. Even cultured pearls after human intervention are created by nature. Visitors will be amazed to learn that, in principle, any mollusc can produce a pearl from the giant clam to the land snail, and they will be dazzled by the variety of shapes and colours of pearls.

The history of the trade of pearls between continents is fascinating, and how East and West share the same passion for pearls.

Pearls have a unique symbolic significance and mystique. Can the pearl claim to be the world's favourite gem?

Incredibly, pearls have created a global fascination over millennia, like no other gem. There is something magical about pearls, their beauty lies in their perfection of form and most of all lustre. They are born in the form that nature made them with a natural sheen.

Pearls have always been a symbol of femininity. Maybe this is the reason why the fashion for pearls continues today.

The exhibition showcases many famous examples of pearl jewellery, many styles of which are still being referenced today in popular culture. Have we already seen a 'golden age' of pearl jewellery design or is the pearl a gem that will be constantly reinvented?

Yes, as no other gem has been worn as consistently, as pearls. Pearls are neutral and versatile, appropriate for any occasion. In previous years jewellers have shown a persistent, if not renewed interest in creating new designs with pearls.

What is the most striking or surprising aspect for you about the history of the pearl?

The fascination for pearls and wish to wear these beauties of nature transcends cultures and borders. The similarities in the myths and legends surrounding the pearl in East and West are astonishing. Pearls mark authority and power, symbolize prosperity and on a more personal note they are associated with joy at weddings or tears as a sign of mourning.

Natural pearls have undergone a renaissance in the last decade, achieving spectacular prices at auction, and cultured pearls are being produced in better, more diverse and beautiful qualities. What does the future hold for this gem?

The future of the pearl depends on so many factors, not least the condition of our seas. Natural pearls are simply too rare and expensive, only affordable to the very few. Today China produces such quantities of cultured pearls of inferior quality, that they are endangering the pearl market. Whilst they give great care when creating one pearl from an oyster, the Chinese produce 50 in one mussel, at low cost in rice fields or near housing estates. In South East Asia the farms which produce the beautiful South Sea pearls are experiencing not only financial difficulties but the effects of pollution and for these reasons their future remains uncertain.

The desire for pearls has been so insatiable that imitation pearls have existed over centuries and their advocate in the 1930s Coco Chanel was instrumental in reviving the fashion for pearls and revived the industry at a time when this was unthinkable. No one can tell what the future will hold for this beautiful gem, but the fashion for pearls endures.

The 'Pearls, V&A and Qatar Museums Authority Exhibition', runs from 21 September 2013 to 19 January 2014 as part of the Qatar UK 2013 Year of Culture.

To learn more about the exhibition, visit the V&A website here.

-

Fascinated by Pearls: William Saville-Kent

Fascinated by Pearls: William Saville-Kent

One of the most influential and unsung pioneers of the modern day cultured pearl industry was an Englishman called William Saville-Kent.

Many popularly associate Kokichi Mikimoto with the discovery of the technique to culture a spherical pearl in the early 20th century. But the intriguing truth of the race to discover how to mimic nature's process of creating a spherical pearl is far less clear, even today.

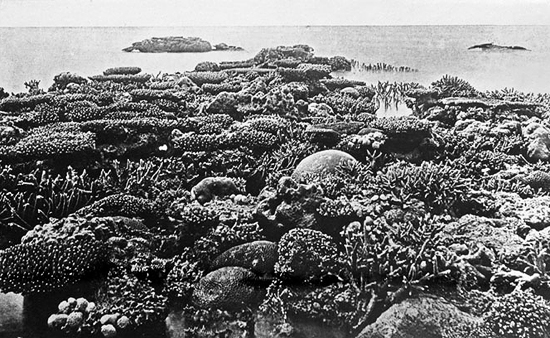

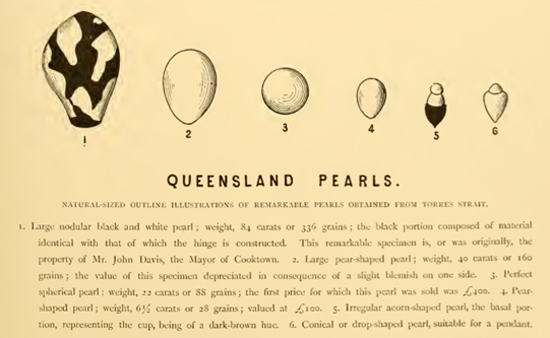

By the late 1890s, the pearling industry in Queensland, Australia was in real trouble. Although the sixth largest industry in Queensland in 1884, its export value had almost halved within the next 5 years. The coral and oyster beds off the northern coasts of Australia and the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea were sadly being depleted by divers and fishing fleets in search of valuable natural pearls and mother-of-pearl shell for use as buttons.

William Saville-Kent was a marine biologist with considerable experience of surveying and managing fish and oyster stocks. Over a period of 15 years, he was appointed by the British Colonial Government as Inspector of Fisheries in Tasmania (1884-87) and Commissioner of Fisheries for both Queensland (1889-92) and Western Australia (1892-95).

One of his main roles was to report on the increasingly difficult economic and environmental situation facing the pearling industry, introducing systems for licensing fishers, regulations for protecting the smaller sizes of the catch and creating protected government reserves for the longer-term sustainability of this natural resource.

Saville-Kent was also a practical naturalist and was the first to recognise the difference between the silver and gold-lipped Pinctada maxima South Sea pearl oyster and the black-lipped Pinctada margaritifera cumingii Tahitian pearl oyster.

Beginning his experiments in 1889 at Thursday Island in the Torres Strait, the centre of the Queensland pearling industry, Saville-Kent would have been very aware of the impact that his work could have on the industry that he was so fascinated with. In this extract above from his 1893 book The Great Barrier Reef, he describes a single perfect spherical pearl (number 3) with a market value then of £400, worth approximately £40,000 adjusted for inflation today.

By 1891, Saville-Kent had successfully produced a number of cultured blister pearls and exhibited these in London. This was two years before Mikimoto had cultured five semi-spherical pearls in Japan.

Returning from London in 1905, with a syndicate called 'The Natural Pearl Shell Cultivation Company of London', a commercial cultured pearl farm was established near Torres Straits. Saville-Kent and his financial backers were convinced that they had the secret of how to produce a spherical cultured pearl.

There were by now others, however, with the same objective and this unique commercial and scientific race had begun...

-

1920s Jewellery Style and Inspiration

1920s Jewellery Style and Inspiration

Modernism characterised the style of 1920s jewellery, inspiring design even today with its bold, geometric lines and forms.

Following the end of World War I, this decade saw increasingly prosperous times and technological advances. Most of the creative arts sought a break from the past and looked for new directions.

In fashion, it was the decade of the Roaring Twenties with working women wearing more comfortable and practical clothes with slim, streamlined designs. Jewellery was also no exception with a number of important changes and developments.

BAUHAUS AND ART DECO

In the 1920s jewellery broke away from the romantic and elaborate, natural forms and arabesque designs of the Art Nouveau movement of 1890-1910 (during the "Belle Epoque").

In this new decade, jewellery was stripped back bare to its geometric shapes.

Aesthetic clean lines were inspired by designs found in industrial machines. A key influence of this modernism was the influential Bauhaus movement, with its philosophy of form following function.

Contrasting textures and colour were also in fashion. Examples of changing tastes in design were the use of diamonds being set against onyx or translucid citrines and amethysts juxtaposed against opaque coral and jade.

COSTUME JEWELLERY

Fashion designer Coco Chanel broke away from real gemstones with cheaper glass products. The Maison Gripoix, which still exists today, was an early partner for Coco Chanel in creating a range of glass jewellery. The iconic long pearl rope necklace was a signature piece of faux jewellery created at the time.

Josephine Baker, pictured below at the Folies Bergères in Paris, was an icon for the new Art Deco movement, with her fearless style, slicked down hair and bold earrings, oversized rings and ropes of pearls.

Glass jewellery was still expensive and only became affordable in the 1930s with injection-plastic moulding techniques. But Coco Chanel, by stepping into the world of faux jewellery, in effect launched a future industry of costume jewellery.

MACHINE-CUT GEMSTONES

Until the 1920s, gemstones were hand-cut and hand-polished. With the latest developments in machinery, it also became possible to machine-cut and polish gemstones, generating sharp lines and edges, sparkling facets and complicated new gemstone cuts.

The rectangular baguette-cut became hugely popular around this time, as it complemented the geometric designs of the day.

Jewellery of the 1920s then was an innovative period that would become notable for its stunning, daring design.

At Winterson our Luna Rose Tahitian Pearl Ring evokes the 1920s jewellery style of this creative period. The gold shank of the ring has a geometric, solid shape and an angular, baguette cut pink sapphire.

The unusual aubergine colour of its Tahitian pearl, however, would have been unknown in the 1920s and is perhaps entirely modern too.